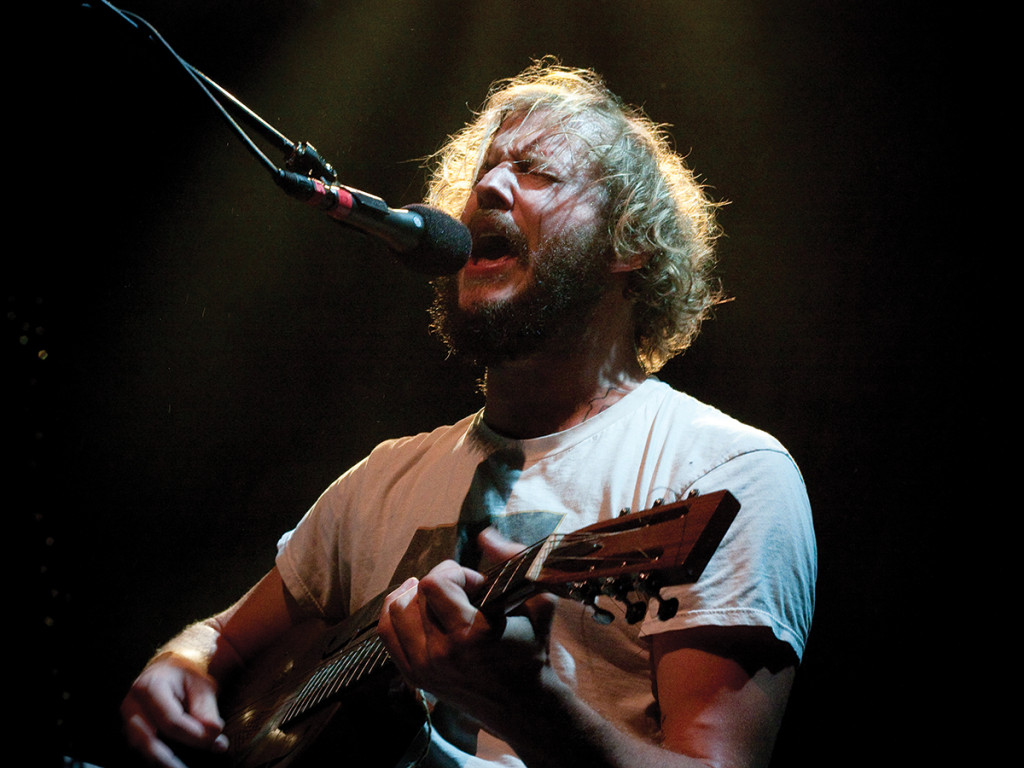

“I felt very exposed. … Not that it was all bad, but it wore down these outer layers, and everything kind of hurt.” That’s Bon Iver frontman Justin Vernon in a recent interview with The New York Times, talking about the explosion of popularity he found himself in the middle of after the release of the band’s second album, “Bon Iver, Bon Iver,” in 2011. That album won the band two Grammys, but Vernon might now be even more renowned for his first effort, 2007’s “For Emma, Forever Ago,” a self-released collection of nine songs anchored by the massively popular “Skinny Love.” Vernon famously recorded the album in his father’s hunting cabin in the forests of Wisconsin, in the middle of winter, alone, recovering from the recent breakup of his former band and his separation from a longtime girlfriend, as well as a case of mononucleosis that had reached his liver.

Vernon is known for three things: Impressionistic lyrics; foggy, sad, immersive atmosphere; and his ghostly falsetto, which he often layers into choir. His melodies navigate meditations on love, loss, regret and memory in a way that is as poignant and exact as anything musical I can think of. This holds especially true for “For Emma, Forever Ago,” whose focused melancholy laid a solid foundation for the expansiveness of the more versatile “Bon Iver, Bon Iver.”

Sometime between the release of the first album and the second, Vernon caught the attention of Kanye West, who featured him on “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy” and “Yeezus,” and who just this past August called Vernon his “favorite living artist.” Now, not to give Kanye too much credit, but as far as I can tell, people don’t generally spend a lot of time around him without coming away altered in ways no one can immediately understand, and, judging by the sound of Bon Iver’s latest album, “22, A Million,” Vernon is no exception.

The notion of vulnerability has surrounded Vernon’s work since Bon Iver’s inception, and with good reason. What Vernon’s voice communicates is mysterious, sensitive, nuanced and never shallow, but it’s somehow so accessible that it feels naked, raw — “exposed,” as he said in the NYT interview. It’s the artistic equivalent of having pupils that won’t constrict, and in the age of star pop factories and the putrefaction of a large swath of the now-gargantuan alternative rock and indie pop scene, it’s not hard to see why so many fans and critics are scared to lose the gloomy, fiercely sensitive lighthouse that has always been the center of Bon Iver’s appeal.

Enter “22, A Million,” with its emphasis on synthesizers, heavy vocoding and a mood that leans toward melancholy but rarely dwells in it, and it shouldn’t come as a huge surprise when it gets a lot of people pissed off, or at least feeling cheated. There are obvious reasons to feel this way; the difference between Bon Iver’s earlier work and “22” can be extremely jarring. Try listening to “For Emma”’s “Flume,” with its grounded chords and attenuated arpeggios, before switching to the new album’s “10 d E A T h b R E a s T,” whose percussion and bass is so compelling, chaotic and dirty that I’m tempted to shower after listening to it.

Strange titles aside, the songs don’t need much help to feel bizarre. Vernon started experimenting with vocoding and autotune years ago, and his love affair seems to have come to a head: The first track, “22 (OVER S∞∞N),” begins with a voice, pitched high and thin, crooning, “It might be over soon.” It’s a neatly packaged message, Vernon telling us that though the style might have changed, the substance hasn’t. Like many other Bon Iver refrains, the line is shot through with ambiguity, a two-sidedness that Vernon says stems partly from his college-age fascination with Taoism’s emphasis on paradoxes and dualism: The line could be a statement of relief and hope, or of apprehension and grief or, of course, all of those things.

One of Vernon’s great strengths is his willingness to experiment with textures, and his ambition is on full display in “22, A Million.” Fidgeting vocal samples squirm out of nowhere and disappear into the perky guitar riff of “666 ʇ”; “21 M◊◊N WATER,” a spacey, indulgent bridge that steers the album toward comfort, sounds as though it consists almost entirely of instrumental byproducts and Valium; “8 (circle)” and “____45_____” both float on a huge cushion of saxophone. Fortunately, Vernon isn’t afraid to scale things back: “715 CR∑∑KS” is two minutes of his thickly vocoded voice singing without accompaniment, and the album’s last track is a Vernon choir exulting over soft piano.

Part of why I love the album so much is that it’s so easy to make fun of — the silly titles; the heavy vocal effects and constant sampling; the sometimes wonkily employed synths; the elaborate fucking-around that constitutes the end of “21 M◊◊N WATER.” A lot of the sound is artificial; a lot of the songs do sound, at first listen, overproduced. But the critics who are wringing their hands over whether or not Vernon’s vulnerability is still intact are wasting their time. Vernon’s experiments, especially the stuff that can come off as silly, really just mark a new kind of vulnerability — a sincerity, a truthfulness about what he wants to do and where he wants to go; and this is more inspiring and more daring than putting out another album of great, haunting, guitar-centered indie rock, no matter how beautiful or transcendent or successful that could have been. Or maybe whatever kind of vulnerability we hear isn’t new at all. Maybe Vernon doesn’t have to be naked; maybe he just has to be honest.

The album’s fifth song, “29 #Strafford APTS,” is its most revealing. Saxophones and a piano sit back in the mix; guitars are softly strummed and plucked under Vernon’s vocals, which are paired with those of his drummer, Sean Carey. The lyrics sketch out a relationship as it falls apart, the narrator holding on by his fingertips, vacillating between despair and the hope of scavenging something. Like most of Bon Iver’s best work, the song is about loss, inadequacy and the ephemerality of love. If that all sounds dumb or banal to you, you’re right — but Vernon and Carey have been working this ground for years, and they pull it off beautifully. Those pining for Bon Iver’s vulnerability need look no further than Carey’s voice in the last chorus: “I hold the note / You wrote and know / You’ve buried all your alimony butterflies.” Everything but the guitar falls away, and Carey begins the lines trembling and bare, muted and fuzzed with what sounds like old vinyl, but then pierces suddenly through to clarity on “butterflies,” kicking down an unlocked door, stumbling into something new.

Rating: 9/10