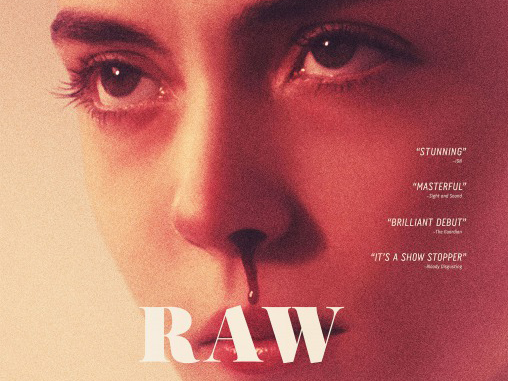

Raw (adj.): (of a material or a substance) In its natural state; unprocessed; a French-Belgian film directed by Julia Ducournau starring Garance Marillier infamous for causing two viewers at Toronto International Film Festival to faint.

“Raw” is about desire. It’s about Justine (Marillier), a college freshman in a veterinary school in France — the same school her veterinarian father (Laurent Lucas) and veterinarian mother (Joanna Preiss) went to, the same school her veterinarian-in-training older sister, Alexia (Ella Rumpf) goes to. A devoted vegetarian like her parents and sister (ostensibly), Justine’s peaceful life is punctured when she is hazed by upperclassmen and made to eat raw meat.

Three times in my 20 years of life have I physically been perturbed by something to the point of physical discomfort — nausea, tunnel vision and a marathon man’s worth of sweat. The first instance was viewing “Guinea Pig: Flowers of Flesh and Blood,” a meritless film solely about torture (don’t watch it). The second was at the Los Angeles Museum of Death, a self-guided tour containing photographic documentation of real-life death. The third time was when I saw one particular scene in “Raw.” Now that may not sound like much of an accolade when objectively measuring a film’s worth, but it sure speaks to the aptness of its title. Folks, “Raw” fucked me up.

“Raw” captures the essence of body horror, which is essentially the fear of losing control over one’s own body, a loss of agency over that which we trust we can depend on. But it really isn’t even a horror film at all. It’s a drama soaked in blood, an allegory that can’t operate without succumbing to carnal desires, one which despite its passing moments of savagery manages to maintain an air of sleek stylization — classiness, even — evident in its brilliant cinematography. Nature serves a pseudo-antagonist role in the film, with no clear explanation as to why Justine goes through her transformation save to expedite the function of her flesh-deprived body. “What are you hungry for?” the film’s poster asks, and Ducournau answers that, equal parts gruesomely, eloquently and subtly. Maybe it’s just meat, sure, but maybe it’s sex, or maybe it’s the termination of the patriarchal society that dominates and hushes such desires; no, wait, nevermind, actually it’s everything, it’s freedom and freedom never looked so depraved.

The film is moreover bolstered by a tour de force from its 19-year-old star: Marillier’s performance carries with it a sharpness that hooks viewers in with her socially inept empathy only to choke them later with an animalistic possession so absorbing to watch unfold.

It’s easy (I know from experience) to judge “Raw” largely on its admittedly annoying oversights, like its heavy reliance on audiences’ willing suspension of disbelief. I’ve never attended veterinary school in France but I can say pretty confidently that the whole hazing process, that vague, stereotypical, hierarchical, fraternity-like structure is bonkers. Like, way out there. The film is peppered with minor annoyances that momentarily obscure from the film’s core strengths but nonetheless deserves placement among the long list of films that get better the more one reflects on it.

Verdict: “Raw” is not without its minor missteps, especially with regards to the plausibility of components both crucial and relatively unimportant to the plot. But Ducournau’s cannibalistic drama is rich in its provocative narrative and fueled by an electrifying performance from Marillier, a harrowing examination of the underfed side of human desire scarcely explored in cinema.