The National Foundation for Infectious Diseases estimates that during the 2017-18 flu season, as many as 80,000 deaths across the United States could be attributed to influenza. With the flu season beginning this October, this year appears to be no different.

The season’s first influenza-related death was an unvaccinated child in Florida on Oct. 15. Since Oct. 15, there have been an additional 34 influenza deaths during the 2018-19 season at the time of this writing as the season starts to truly kick in.

Every year there are fluctuations, but the flu hospitalizes hundreds of thousands of people each year and leads to tens of thousands of deaths. Data from the latest available season, the 2015-16 season, estimates that vaccinations averted 71,479 hospital visits and 2,882 deaths. Despite the continued proven effectiveness and benefits that reassert themselves every year, factors such as apathy and mistrust of proven science continue to keep millions of Americans from getting their necessary inoculations each year. In a culture where vaccination is not highly encouraged or mandated, our collective failure to vaccinate properly comes with serious costs that should not continue to be ignored.

Anyone you ask appears to give no shortage of different answers to why they haven’t gotten a flu shot, but they all boil down to nothing other than apathy or unsubstantiated skepticism regarding the effects of vaccinations.

A nationwide failure to make vaccinations for viruses like the flu compulsory in a similar manner to diseases like measles is in a large degree to blame this country’s millions of flu cases each year, leading to hundreds of thousands of hospitalizations and tens of thousands of fatalities.

While the issue of skepticism is more dangerous and difficult to address in our society, public apathy regarding flu vaccines can be more easily remedied. Less than half of all Americans consistently get their flu shots each year, and more than 80,000 people in America died during the last flu season. 90 percent of the fatalities were over the age of 65, but 180 of the deaths were children and teenagers. While thousands of Americans die each year and less than half of them get their flu shots annually, a much more impressive 91.1 percent of all children aged 19-35 months have been properly vaccinated for measles. The reason being that firstly in early childhood care doctors highly recommend that parents get proper vaccination, and thus provide an accessible outlet to parents that doesn’t require them to take the initiative. Secondly, however, documentation of key vaccinations, including measles, are required to attend school in all 50 states, unless exempted for religious or philosophical reasons in 47 of the 50.

The vaccinations that are compulsory to attend school are of course much more important than the seasonal influenza vaccination, however they illustrate an important point – that by compelling residents to get vaccinated, the public health concerns that stem from these diseases can be largely avoided (at least to a degree of 91 percent). This high rate of vaccination for a particular disease is called herd immunity, and while it differs depending on the infectiousness of the disease, it typically lies somewhere between 90 and 95 percent coverage. The advantages of herd immunity, apart from generally high rates of coverage, are that it is generally recognized as necessary to protect individuals that are unable to be properly vaccinated, for medical reasons or otherwise, from becoming infected.

Apathy around critically important issues will always exist in our society, as evidenced by low voter turnout rates in this country. But the success in achieving herd immunity for measles by generally requiring it for children to attend school, shows how easily vaccination rates can be increased, and save millions of dollars and thousands of lives each year in the process.

Low vaccination rates across the country for less serious but still dangerous viruses like the seasonal flu have no shortage of costly effects. Given these effects, it stands that a nationwide failure to make vaccinations for viruses like the flu compulsory in a similar manner to diseases like measles is in a large degree to blame this country’s millions of flu cases each year, leading to hundreds of thousands of hospitalizations and tens of thousands of fatalities. Increasing accessibility to the flu vaccine and making it a compulsory shot each year could go a long way towards drastically improving public health outcomes in this country.

For more important vaccinations, like measles or smallpox, most people are vaccinated due to stronger societal pressures or obligations to get these vaccinations. Yet a dangerous number of individuals and families still remain exposed and unprotected. While the increased pressure is largely successful in overcoming the apathy barrier for individuals, it still fails to make sure vaccine skeptics get their most important inoculations.

The most insidious obstacle that stands in the way of increasing vaccination rates in this country is the shockingly prevalent degree of mistrust and skepticism and proven scientific knowledge that clearly illustrates the benefit and necessity of vaccinations in our society. For more important vaccinations, like measles or smallpox, most people are vaccinated due to stronger societal pressures or obligations to get these vaccinations, yet a dangerous number of individuals and families still remain exposed and unprotected. While the increased pressure is largely successful in overcoming the apathy barrier for individuals, it still fails to make sure vaccine skeptics get their most important inoculations.

The most pervasive iteration of this vaccine skepticism comes from an infamous paper from 1998 that alleged a link between vaccinations for measles, mumps and rubella and autism in children. The paper has been repeatedly debunked by the medical community and has even been flagged as research fraud, but as with any outrageous falsehood, it has traveled much faster and farther than any corrections that have followed. The physician that published the paper, Andrew Wakefield, has since had his medical license revoked, yet his nefarious paper has had serious consequences.

All Americans, from individual UCR students to campus administration to the federal government, should seriously commit to increasing vaccination rates as much as possible. The lives of our neighbors and families may depend on it.

One survey by the National Consumers League, a consumer advocacy organization, found that as many as 35 percent of American parents believe that “vaccines can cause autism.” Estimates show that as a result of this fear among others, about one third of all North American parents “are hesitant to get their children vaccinated.”

Mistrust or fear of vaccines and the science behind them is much more difficult to address than simple apathy. For example, parents that fear the effects of vaccines will attempt to obtain religious or philosophical exemptions from vaccinations that are made compulsory. Evidence suggests that this is already very common among mandatory vaccinations and actually appears to be growing as a trend. One school in Oregon has lower toddler vaccination rates than the national rate of Venezuela. Most of these highly unvaccinated enclaves are also relatively affluent and thus presumably educated neighborhoods, like suburbs around Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago and New York.

This troubling dynamic clearly points to a failure of our education system to some degree if such a basic understanding of simple science is lacking for some of our even most educated residents. The answers may be difficult to find, but something clearly has to change in our education system that reaffirms the value and certainty of science, particularly the broad knowledge of scientific consensus.

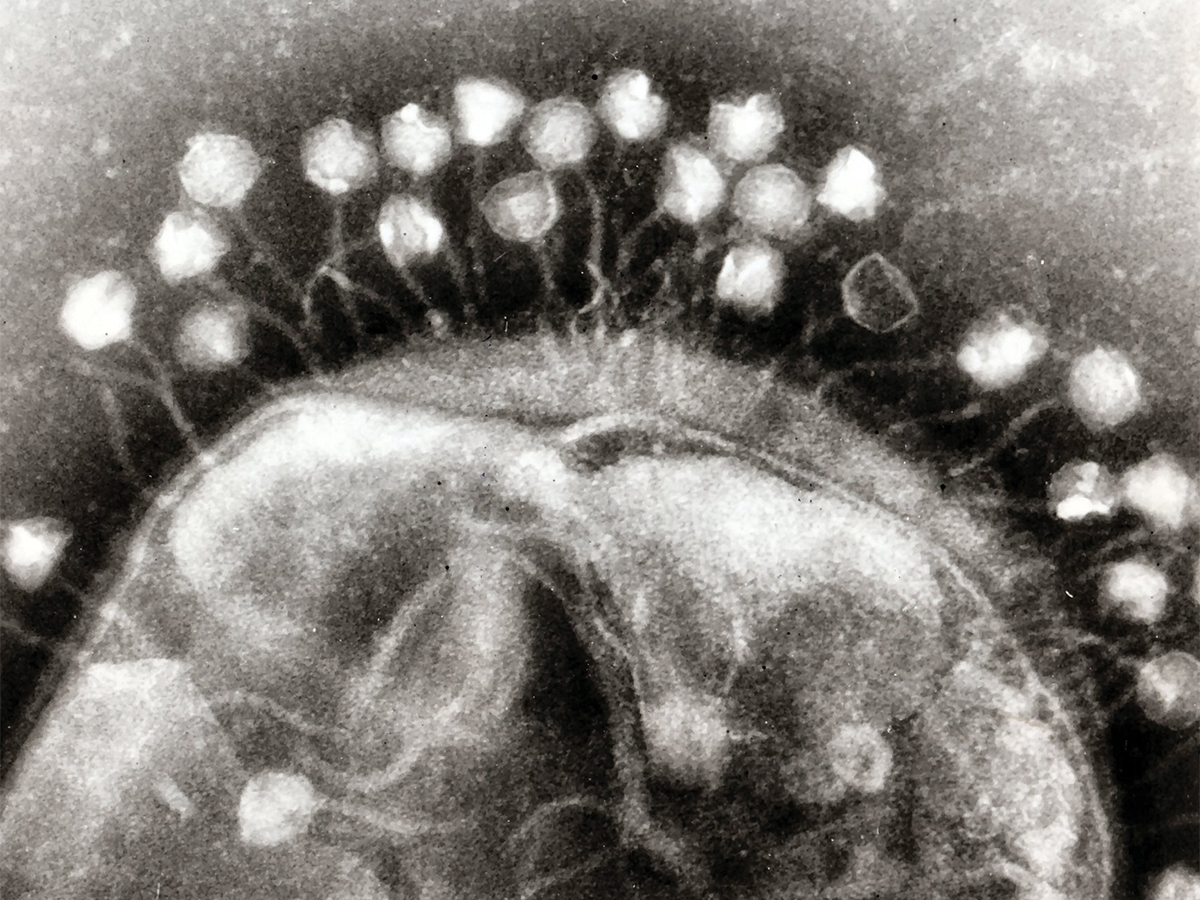

After all, the science of vaccines is relatively simple. The body is most effective at fending off foreign microbes by countering them with antibodies, or miniscule immune cells that mark invading cells for destruction by the body. The primary challenges our immune systems face in deterring foreign microbes, or antigens, is producing proper antibodies to properly identify antigens that pose a threat to our bodies. When we have recently fended off a disease or virus, our body becomes familiar with the antibodies necessary to mark the antigens, and thus our bodies are highly unlikely to become infected for as long as the antibodies remain. What a vaccination does, is inject an inert version of the very virus it protects against. By doing so, it allows our body to prepare and produce the necessary antibodies to protect against the infection without the risk of actually contracting it.

The science of vaccines is also fascinating; it’s a shame that so many Americans don’t properly understand or appreciate this simple miracle of human ingenuity that brought an end to the terror of smallpox, which killed more than 300 million in just the 20th century. Stronger government action to make vaccines more accessible and compulsory is a simple and prudent course of action that would bring wide benefits, yet answers to the issue of science skepticism prove more elusive. For starters, institutions like UCR could start by better advertising the availability of flu shots on campus at the Student Health Center, and more states should follow California’s lead by refusing to allow religious or philosophical exemptions from jeopardizing the safety of themselves, their children or the entire population, or herd.

As we grow increasingly disconnected from the consequences of poor vaccination from decades past, it is easy to become increasingly apathetic about vaccines. What is shocking, however, is that we are seeing early signs of the decline of herd immunity and increasing cases of unnecessary infections nationwide. All Americans, from individual UCR students to campus administration to the federal government, should seriously commit to increasing vaccination rates as much as possible. The lives of our neighbors and families may depend on it.