One of the most esteemed video game franchises of all time is no doubt Nintendo’s very own Legend of Zelda series; one that spans over three decades! With such a deep history comes a very interesting, weird and awful past. Nintendo certainly made mistakes in 1993 with high hopes after the smash success of “The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past.” A game that sold well into the 10 millions, in deep contrast to Nintendo’s attempt at branching out with Zelda games on the failed CD-I by Phillips. It’s from that mishap that not even five years later Nintendo would create “The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time” (OOT). Christened as a contender for the greatest (and glitchiest) game of all time, it’s an achievement that led Nintendo to even greater heights by moving outside of their players’ comfort zone. The series always had some darker elements and scarier moments, but nothing compared to the deeply depressing and downright tragic themes prevalent through the sixth main installment in the Zelda franchise, “The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask” (MM).

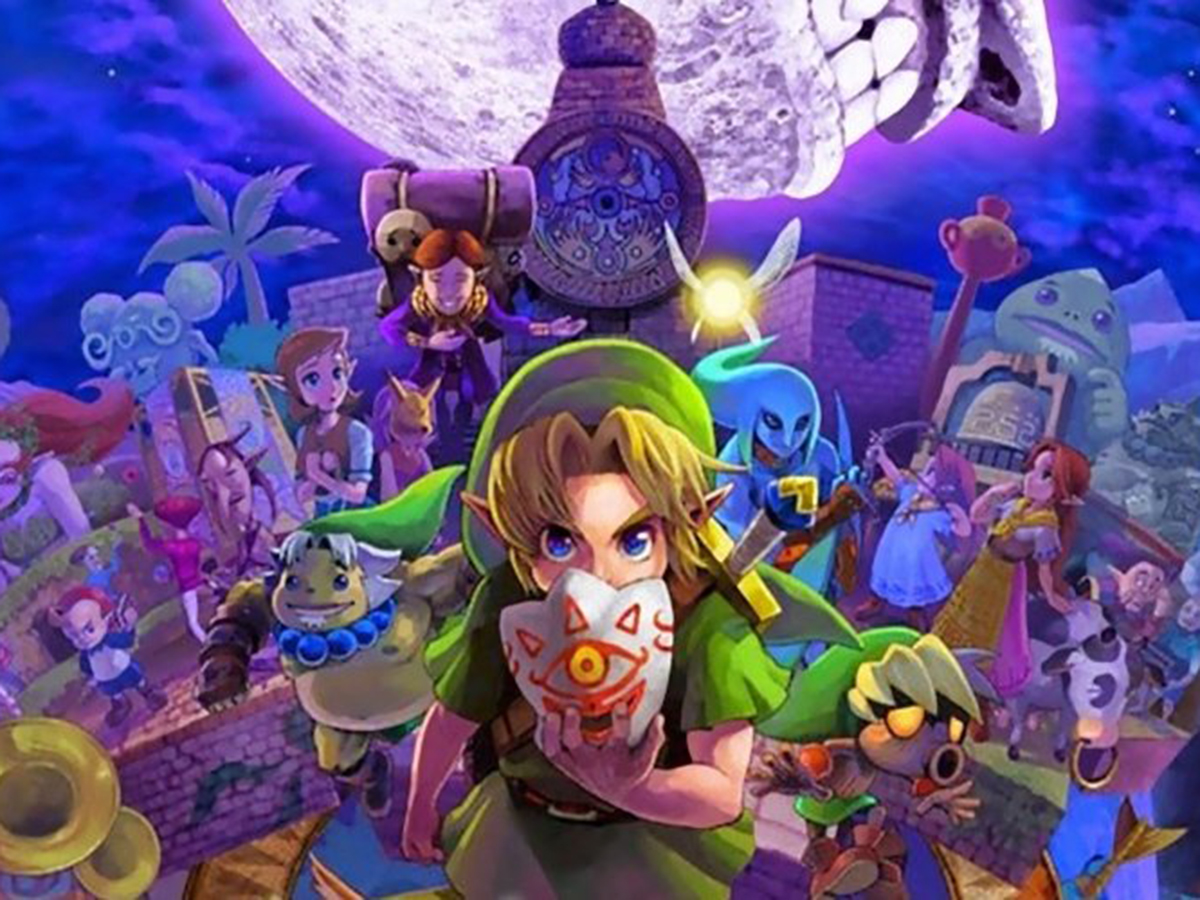

The title is certainly worthy of succeeding OOT. After all, the legendary title’s little brother needs to prove its worth. It takes place after Link, The Hero of Time, sets off to find his missing companion, a fairy named Navi. On this journey he’s hassled by Skull Kid who dons the infamously evil Majora’s Mask. The dark powers of the mask influences those behind it to do its bidding and work toward its cataclysmic desires. Link of course gives chase after Skull Kid steals the Ocarina of Time. As such, the nefarious being utilizes that dark magic to transform Link into a Deku Scrub, a small woodland creature with limited abilities. Link is subsequently introduced to a new land called Termina, a place fraught with torment. At the center of it all is Clock Town, while looking grim the place is quite busy; the annual Carnival of Time is in three days which celebrates the sun aligning itself with the moon. Seemingly, the moon has become the center of attention due to how close it is to crashing into Clock Town. The townspeople are either denying its possibility or outright panicking; yet life goes on and people still work. Skull Kid’s ultimate plan is to decimate the world and send the moon into Termina. The land is in panic as the four main kingdoms are in hysteria; thus it’s up to Link to stop Skull Kid and help the world around him as much as possible.

Already, from this brief synopsis, it’s easy to notice how different in tone the main setup and world is just from a glance. Even the name Termina has countless metaphors and ideas behind it, much like the lives and problems the people that inhabit this world have. In fact, the name comes from director, Eiji Aounoma who came up with the term from the word Terminal. It’s almost as if he’s implying that the world is seemingly the terminal between life and death where spirits go to find their way home. Most Zelda games are paced in a way that has Link learning of his importance to save the world from Ganondorf using the power of the Triforce. The buildup in this title comes from playing OOT, but it switches the perspectives of everything. Link is still thrusted into the unknown, but this time as an outsider in a very populated place. Hyrule is basically only known for having one densely populated area in Castle Town which is incomparable to how large Clock Town is. Not to mention just how dense it feels with each person, passerby and side character having their own story, quests, life and struggles. For example, there’s a swordmaster living in Clock Town who can teach Link new abilities. Yet during the final hours before moonfall, he cowers in fear over the thought of death. Many of these quests can be summed up as side distractions to get more health and rewards, but in MM, these quests populate the world around Link and highlight a very gloomy world.

Majora’s Mask has a strange gameplay loop and mechanic that sets the pace for the game. With time being of the essence, Link utilizes the Ocarina of Time (after taking it back from Skull Kid) to reset the clock back to the first day thus creating a loop for the games events to infinitely replay. Yet, that’s not the only musical number Link learns as the Song of Healing has quite a lot of purpose as well. Over the course of the story, Link comes to learn about the various kingdoms’ issues and problems they face; usually revolving around a person failing in their duties to help those around them. An example of this takes place in an abandoned house, where Link meets a little girl and her father who has almost been turned into a Gibdo, a terrifying mummified creature. The girl is terrified and sends Link downstairs to confront the half-mummified man. Playing the song of healing of course returns him to his normal self, but what remains are the trapped remnants of a gibdo protected in a mask. A heartwarming resolution that leaves behind a terrifying mask and memory.

Bringing the people to peace whether it be with songs or dungeon crawling is a rewardingly hopeful silver lining to the tone of the title. As the name implies, Majora’s Mask is a collectathon with many different masks for Link to look for and collect. Some masks have no usability, others have lots of potential but some tell stories that only those who listen will ever know. It’s captivating in the most unsettling moments that will have players on edge the entire way through. For 20 years, this game’s themes and messages are reverberated in so many other Nintendo titles. Replay “The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask,” it’s a superb title and has remained influential for taking the series in a new direction by bringing the series to it’s most petrifying moments.