In 1989, Taiwanese auteur Hou Hsiao-Hsien told the story of a family in the small coastal town of Jiufen. Without context, the film appears to be surrounded by an impenetrable veil of mysticism. However, those familiar with the island’s history will understand the significance within the specific release date of “A City of Sadness.” To unlock the importance of the film, we must use a key, one that was forged on Aug. 15, 1945.

A radio broadcast blares. Emperor Hirohito has just announced the unconditional surrender of Japan, ending 50 years of colonial rule. The streets are paved with joy, for Taiwan is free again. Unbeknownst to many, the ongoing feud between the Chinese Communist Party and Kuomintang (Nationalists) will prove to be as dangerous as the previous war. With the Republic of China now in control of Taiwan, the threat of the suppressive regime grows larger by the day.

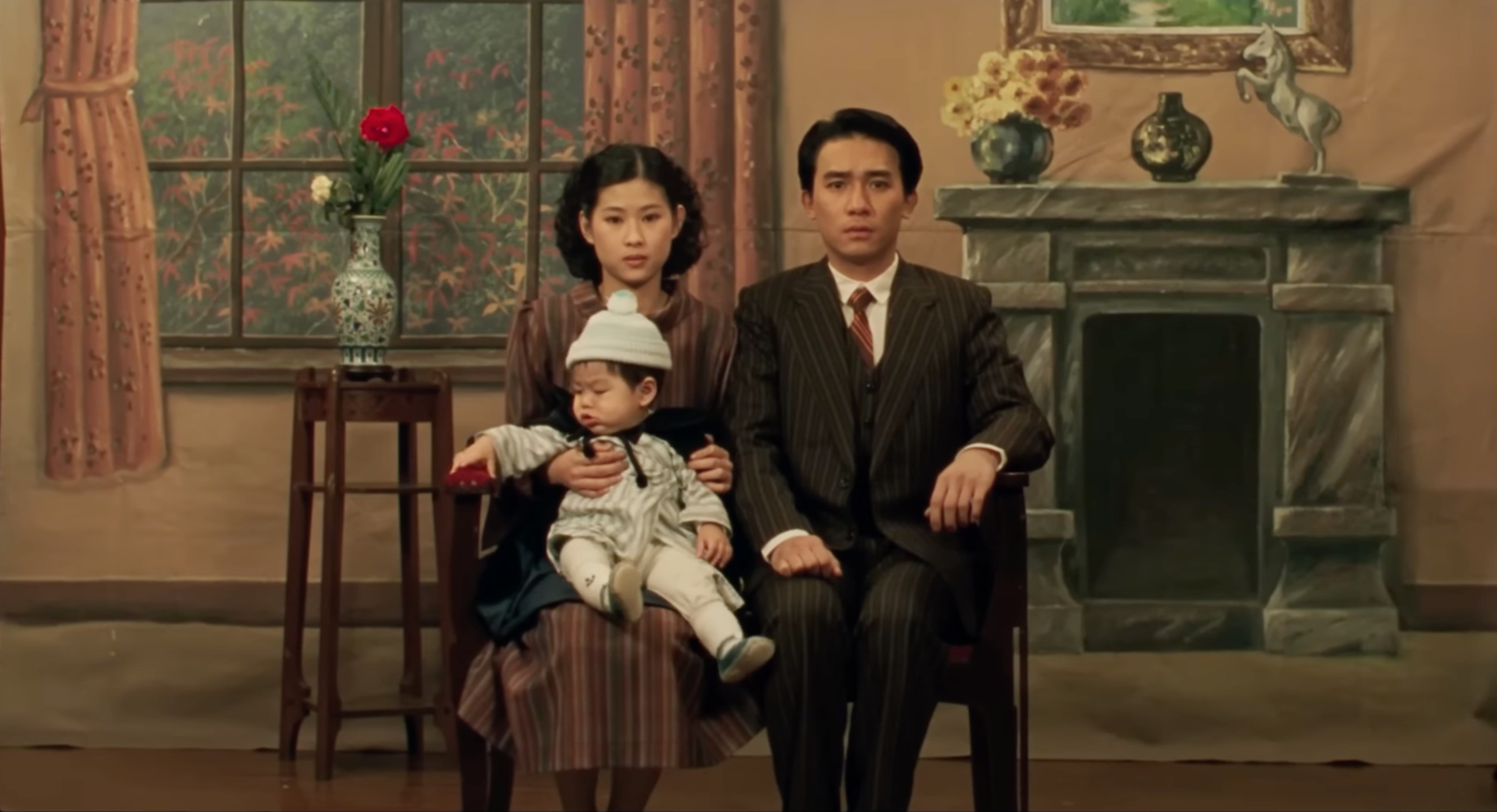

The audience witnesses the shift in the political climate through the daily lives of the Lin family. Wen-ching, the youngest of four brothers, is a photographer with leftist beliefs and is also deaf. The third brother, Wen-leung, is scarred by his time in World War II. The second brother has vanished, while the eldest runs an underground nightclub and a smuggling business. Any sense of normalcy the family has is slowly upended, as the external threat of governmental force proves to destroy their lives from within. Hou’s direction stifles any drastic camera movement, with shots often containing a sense of voyeurism; it is as if the viewer is a ghost floating adrift in the past. Precision is the utmost priority, with silence often containing more meaning than speech.

As the Kuomintang continues to abuse their power, each member of the family is increasingly exposed to danger. Hiromi and Hiroe are two siblings with contrasting personalities. One wants to live in peace, while the other seeks to fight back. Showcasing much of the story through Hiromi’s point of view sheds light on the value of a female-centric perspective, as well as highlighting a group that many would have thought to be safe from marginalization. It soon becomes evident that people’s safety of all backgrounds is at risk.

Wen-ching uses communication through written characters — a clever choice that Hou takes advantage of for a multitude of reasons. The character is played by iconic Hong Kong actor Tony Leung Chiu-wai, who was unable to speak the prominent languages featured in the film. Wen-ching’s writing serves as a link between the events not shown on screen and the viewer’s thoughts, coinciding with the narrative’s slow, detail-oriented pace. Long, drawn-out notes are implemented throughout the soundtrack, acting as a cry for help. Physical expression rather than dialogue is employed with the intent of revealing the widespread manifestation of pain that the citizens go through. The audience sees this on display through the aftermath of Wen-leung’s torture, Wen-heung’s eventual death and the constant sense of melancholy in Wen-ching’s eyes.

Later on, the Lin family listens to another radio broadcast. The built-up tension between the Kuomintang and the native population is about to explode in a catharsis of violence. Hou uses familiar images to contrast the once peaceful state of the local hospital, transitioning it into a nest of terror, one filled with bloody stretchers and gut-wrenching screams.

The rich yet eerie cinematography is complemented by the frequent use of passageways, a technique coined by the legendary Japanese filmmaker Yasujirō Ozu, which Hou applies to establish the deteriorating relationship between the environment and those who inhabit it. People are arrested and beaten. Any protests are put down, resulting in the death of at least 18,000 people, and martial law is twice declared and lifted during this time. However, there are no direct depictions of the atrocities committed.

This seemingly limited but nuanced portrayal of the 228 incident is the first instance in history the event was addressed on film, a feat even more impressive due to the lack of books written about the subject. The long-term establishment of martial law instituted briefly after the incident only ended two years before the release of “A City of Sadness,” making Hou’s calculated chronicle all the more consequential.

The impact of Hou’s remarkable film runs even deeper once one realizes the importance of speaking for the voiceless. Through the portrayal of a common family, an entire generation’s story became unearthed, providing hope for a world where justice prevails. While art will never be able to remedy the scars of the past, it certainly has the potential to heal them, all while cementing the truth in its creative process.