Adaptations and remakes are ever-increasing in their frequency throughout the modern landscape of film. Every so often, a spectacular, wholly original experience is birthed from the ashes of an older work — “Carmen” being the most recent example. A vivid reimagination of French composer Georges Bizet’s four-act opera, the film assumes a completely new identity through the assembling of various acts of physical expression. Engaging cinematic techniques and the art of dancing work in conjunction with each other to form a magical atmosphere. Director Benjamin Millepied’s intentions are laser-focused from the start — let one’s emotions speak for themselves.

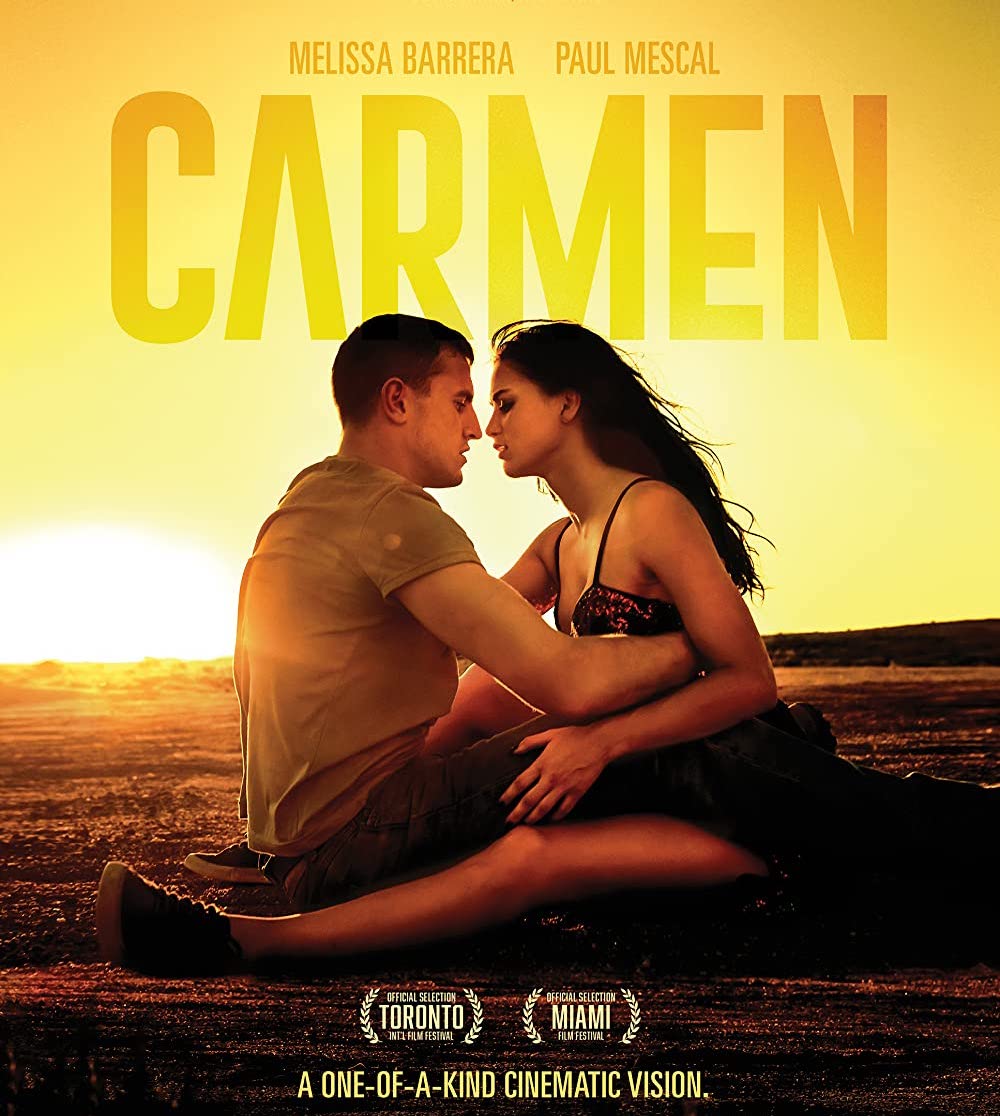

Millepied’s extensive background as a dancer and choreographer, having worked on notable works such as “Black Swan,” translates itself into the focus of “Carmen’s” story. Carmen (Melissa Barrera) is a young Mexican woman who escapes her home in the aftermath of a dangerous situation, her path eventually intertwining with Aidan (Paul Mescal), an American border patrol agent. Much of the runtime is spent establishing the scenery, sometimes leaving a seemingly intentional disconnect between the audience and the budding love between the pair. Starting from an inherently political standpoint, the film begins to stray away from any sort of ideological stance by the second act, coinciding with the formation of Millepied’s then-clear directorial vision.

Those who favor exercises in visual beauty rather than detailed stories will have an easier time appreciating the film’s repeated exhibitionism. Audiences who may have expected a different approach may also find it to be slow, but the soundscape’s meshing with the images will not disappoint. As a result of this, the quality and depth of the character-driven screenplay take a backseat, allowing its attempted resonance to propel the viewer’s engagement.

Jörg Widmer’s ethereal cinematography is central to the film’s success, as he creates a dynamic landscape out of a plethora of locations. This comingling of both nature and physical force is borne out of the combination of two of his past works, “A Hidden Life” and “Pina.” Terrence Malick and Wim Wenders, the directors of the aforementioned works, are masters of the cinematic craft and work closely with their Directors of Photography to establish their respective distinguishable styles. Widmer undoubtedly used the spirit of those films to portray human emotion and its connection with one’s tangible surroundings, a recurring theme in those films. The result is a brilliant amalgamation of otherworldly glimpses of wonder and the dark, claustrophobic parts of a recurring nightmare.

Barrera’s widespread musical talents expand upon themselves within her role, both honing a familiar craft and displaying her ability to master a new skill. Although “In The Heights” and “Carmen” are both musicals in their own right, the latter places a greater emphasis on dancing, forcing the music to fuel the performance, not the narrative. Her elegant dancing is led by an element of innate grace. Raw energy is channeled into each movement, with the lighting and composition flowing alongside this; there is not a moment where one would believe she is not an experienced performer. Her screen presence is palpable, with the challenge of taking on a wide array of emotions proving to be an easy feat.

Mescal’s subtlety shines once again, and despite having significantly fewer dancing scenes than Barrera, he manages to make his mark. Guarding emotion is what he does so well — his almost abnormal likening for focused silence juxtaposes itself with the overwhelmingly emotive gestures of his counterpart. His second foray into a climatic, final act dance scene in his filmography, one of the most creative parts of the film, takes a different approach. The parallels between dance and violence are highlighted in this bare-knuckle boxing sequence, highlighting the imminent catharsis his character finally achieves.

However, the importance of Nicholas Britell’s grand score cannot be understated. The swelling and raw feel capture the perfect amount of inspiration from the source material while utilizing its specific setting as an opportunity to showcase a different culture. Barrera’s dance indoor sequence (featuring brilliant long takes) perhaps best showcases the delicate side of the composition, while the constant running further enhances the hectic tone present on the outside. Spoken word, traditional opera and tap dancing all make an appearance and operate together cleanly.

While “Carmen” may not have the expected structure of a dance-centric film such as Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1948 classic “The Red Shoes,” it achieves exactly what it sets out to do. Catering to our souls by demonstrating the propensity of art and its malleability, there is no doubt that its unique nature sets it apart from any other film with a similar subject matter. Refreshing at its core, the film challenges the conventional of the traditional musical, being successful in its presentation’s alluring persuasion. Let the wind blow you away, and dance among the desert.

Verdict: Although the lack of a heavy narrative may dissuade some, “Carmen” is a one-of-a-kind breath of fresh air propelled by its ambition.