There was once a time when UCR students couldn’t even elect their own student body president. Only senators were directly elected, and those senators selected the president from amongst themselves. Furthermore, senators had the final say on everything—there was no external balance to ensure that the votes were properly taken. The very structure of the student government lent itself to nepotism and shady dealings, not transparency.

This was not a relic of a long bygone era at UCR. That time was only last academic year.

ASUCR decided to take the brave step forward and make the fundamental structural change necessary to be able to function more effectively as a student body. So they pushed for a new constitution in 2012 that would alter the structure of that body from a parliamentary system to a presidential system, with three branches of government that would provide checks and balances on one another, just like the United States government.

Instead of the senate choosing executive officers, the student body would be able to select an executive cabinet, taking power that once rested in the senate and returning it to the student body. The executive branch would gain veto power over the legislative branch to help prevent bills from being ramrodded through in a hasty legislative session. A newly-created judicial branch would oversee the operation of the new student government and ensure that it followed the ASUCR Constitution and Bylaws. This restructuring was, according to the text of the proposed change, “a necessary change to respond to the growing undergraduate student population and political interest, the growing political issues, and to the principle of defending our autonomy from the administration.”

And it was necessary. The Highlander endorsed the change, and so did the student body of UCR. The new constitution passed overwhelmingly with 80 percent of student support. 2,665 students voted in favor of the new constitution, just about 300 votes shy of the total student turnout in this year’s set of elections. ASUCR received an unprecedented mandate to implement a new system of government that would make it more effective, more transparent and more responsive to UCR students.

This year, now that the new system is in place, one would hope to see a more transparent ASUCR like the constitutional change promised. Instead, ASUCR has been buffeted by controversy arising from secret votes and the fallout of recklessly voting on emotionally-sensitive legislation.

But this is not because the constitutional change failed. It is instead due to the fact that the changes have not been sufficiently implemented to live up to the constitution’s promise of separation of powers.

In response to the secrecy surrounding the Divestment from Companies that Profit from Apartheid resolution that would call for the UC to divest from companies investing in Israel, the long-dormant judicial branch activated itself. Ruling that ASUCR had violated the required reading bylaw in the run-up to the vote, the judicial branch presented the senate with a list of reforms that would prevent the conflicts from recurring.

Just as the constitutional change intended, the judicial branch provided much-needed oversight over murky senatorial procedures. Now it is up to the senate to uphold its part of the bargain. When Vice Justice Mark Orland made his presentation to the senate, many senators recognized the authority of the judiciary as granted by the ASUCR Constitution and gave all indications to show they would follow the ruling.

Senators did raise concerns about the content and implementation of the reforms, and those are valid questions. But it was troubling to hear some senators’ objections not to the content of the ruling, but to the fact that the ruling was issued in the first place, and that the senate and executive branch would have to abide by it.

The objections are grounded in two assumptions. First, it assumes that the judiciary does not have the power to rule on this issue in the first place. Second, it assumes the ruling by the judiciary is not final.

But as anyone who has read the ASUCR Constitution knows, these assumptions are not grounded in truth. The judicial branch does indeed have the power to make rulings on whether or not ASUCR has violated its constitution. As clearly stated in Article VI, Section A, the judiciary’s authority “shall extend to all judicial cases, as defined herein, arising under this Constitution, the ASUCR Bylaws, official actions of ASUCR executive officers, employees, and the Senate, and any matters delegated to the council by the ASUCR Senate or this Constitution.” The judicial branch identified that the senate’s actions were in conflict with the required reading bylaw, and as such, the judiciary has authority over the case.

Furthermore, the executive branch and legislative branch are both obligated to obey the judicial ruling. Article VI, Section E sums this up succinctly: “All decisions from the Judicial Council shall be final unless reversed by subsequent council action.” Only the judicial branch can overturn rulings by the judicial branch. Just like the Supreme Court of the United States, the ruling of ASUCR’s judiciary is the final interpretation of the law and the constitution.

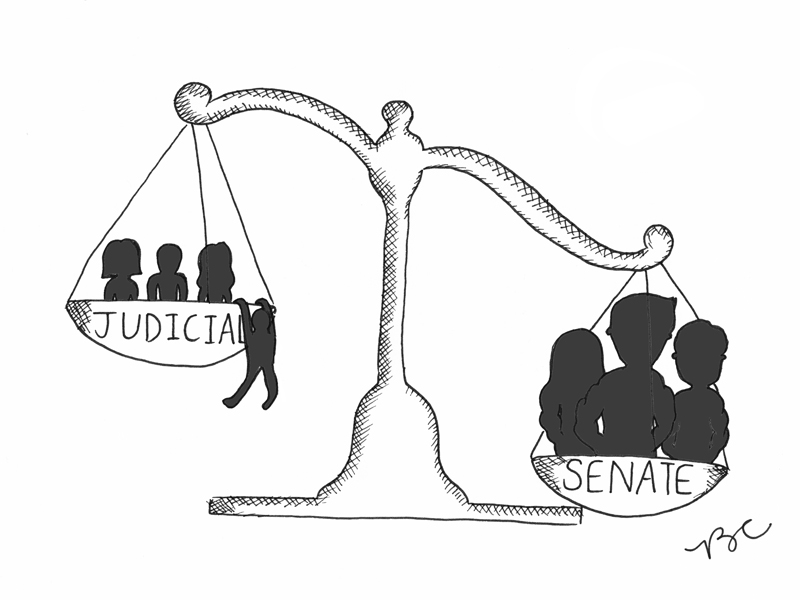

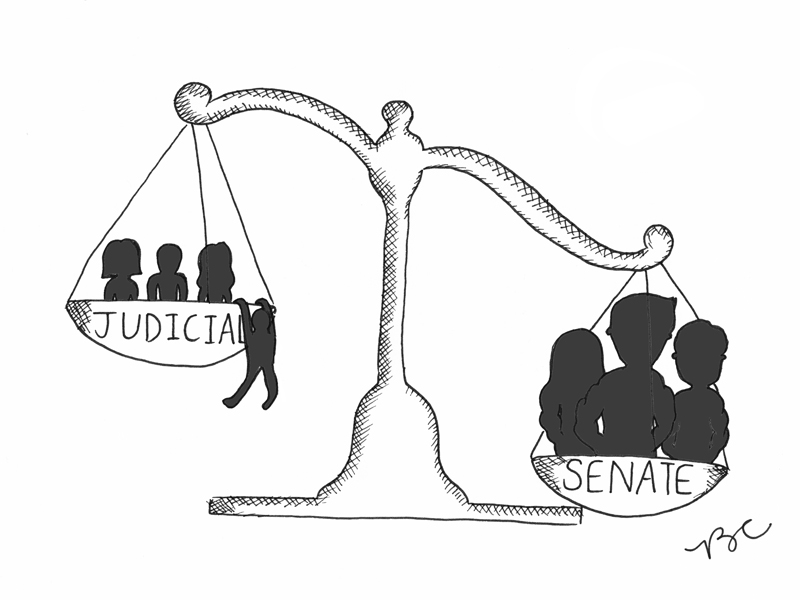

This view of the senate as all-powerful shows a fundamental disregard for the ASUCR Constitution and the idea of separation of powers it has tried to implement. If all the judiciary is allowed to do is make a mild-mannered plea with senators to please change their actions, the whole point of having a judiciary to create accountability to students and the ASUCR Constitution is defeated. The framers of the ASUCR Constitution intended to keep a check on the power of the legislative and executive branches, and the judicial branch is only fulfilling this intent.

And how would the senate look if it blatantly decided to ignore the ruling of the judicial branch? Senators have pledged to further accountability and transparency within ASUCR, but discounting the judicial branch would show students that senators don’t care about being held to task. ASUCR advocates for an engaged student body, but why should students participate in ASUCR if it isn’t accountable to students?

The key to the success of a three-branch system of government is the separation of powers between all three branches. Just like a three-legged stool would collapse if any of its legs were cut off, so too would a three-branch student government be dysfunctional if the judicial branch were ignored. ASUCR must make good on the promise it made to students who voted five-to-one last year in favor of a new constitution, and respect the boundaries of each branch of student government. That way, students can have a government they can truly believe in.