For too long, Taiwan has relied on the goodwill of Washington to aid its defense interests against the impending threat of Beijing and its claims to retake the self-governed island, by force if necessary.

For too long, Taiwan has relied on the goodwill of Washington to aid its defense interests against the impending threat of Beijing and its claims to retake the self-governed island, by force if necessary.

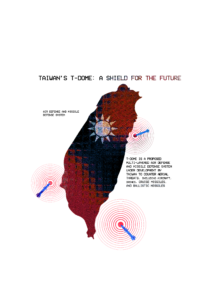

President Lai Ching-Te, a fierce advocate for pro-Taiwanese independence and who has sought Washington’s support since his inauguration in 2024, announced that Taiwan will begin work on its “T-Dome,” a new multi-layered missile shield and air defense system designed to intercept and defend against “hostile threats,” on the National Day of the Republic of China (ROC), Oct. 10.

This comes a day after Taipei’s government warned that Beijing is increasing its capabilities to launch an offensive against the island. Additionally, a French report revealed covert military cooperation between Israel and Taiwan, in which Israel assisted in developing Taiwan’s new “T-Dome,” which is modeled directly after Israel’s effective “Iron Dome” defense system. This strategic collaboration came to light after it was revealed that Taiwan’s deputy defense minister covertly visited Israel in Sep. 2025 to discuss the details of the project.

Taiwan’s current air defense system uses United States (U.S.) produced patriot missiles, the same used by Ukraine since 2023 against Russia’s invasion; the new “T-Dome” seeks to enhance and supersede the island’s current capabilities. Additionally, the construction of a “T-Dome” proves to Washington that Taiwan is committed and capable of sustaining its own defense, as the Trump administration has urged Taiwan to commit up to 10 percent of its GDP on defense, reducing U.S. financial responsibility.

President Lai’s announcement echoes a pervasive fear that many Taiwanese feel: the day Beijing launches an invasion to “reunify” the island with Mainland China. Since 1950, Taiwan has effectively operated in self-governance with all the characteristics of an independent state, including its own democratically elected government, currency and armed forces. Beijing sees the island as a breakaway state and has repeatedly laid reunification claims — achieving Beijing’s “one-China principle” — with Taiwan since the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1950, and has not ruled out force, if necessary.

Taiwan, as a key ally and partner, has been historically reliant on the U.S. for its defense since the start of the Cold War, making the island an instrumental part of the strategy of communist containment in East Asia which was directed against the Soviet Union.

Taiwan, as a key ally and partner, has been historically reliant on the U.S. for its defense since the start of the Cold War, making the island an instrumental part of the strategy of communist containment in East Asia which was directed against the Soviet Union.

While relations between the U.S. and Taiwan have evolved from a formal alliance to a reduced version involving unofficial diplomatic ties with strong cultural, commercial and economic relations, the U.S. remains a bulwark against Chinese aggression in the Taiwan Strait.

This can be better understood with the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act, which, importantly, mandates the U.S. must provide Taiwan “with arms of a defensive character” and establishes a policy “to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security, or the social or economic system, of the people on Taiwan.”

Given the shifting direction of the Trump administration’s stance on Taiwan’s regional security and future aid given to the island’s defense, Taiwan must accelerate its own defense efforts with or without support from the White House. It starkly contrasts with that of the Biden administration, which affirmed the U.S. commitment to Taiwan’s defense. Now, the second Trump administration has urged Taiwan to become more responsible for its spending on its defense system.

This is all part of the U.S. policy of “strategic ambiguity,” which involves deterring a Chinese takeover without an explicit defense commitment to Taiwan. The ambitious “T-Dome” plan would require a massive increase in Taiwan’s defense budget, a controversial topic and challenging to pass in an opposition-controlled legislature.

This is all part of the U.S. policy of “strategic ambiguity,” which involves deterring a Chinese takeover without an explicit defense commitment to Taiwan. The ambitious “T-Dome” plan would require a massive increase in Taiwan’s defense budget, a controversial topic and challenging to pass in an opposition-controlled legislature.

The opposition Kuomintang (KMT) party, a pro-cross-strait relations camp, has said that more confrontation isn’t the answer to Beijing. Andrew Hsia, the KMT party vice chairman, stated, “There is no political base for a dialogue between the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Beijing, so there is no dialogue and they’re becoming more hostile towards each other.”

But right now, aspirations for dialogue and diplomacy between Lai’s administration and Beijing seem to be a reach. Lai’s agenda has stayed committed to maintaining Taiwan’s independence and deterring Beijing from its threats to Taiwanese sovereignty. For that reason, there couldn’t be a more crucial time for a “T-Dome.”

Construction for the new missile defense system would also benefit U.S. interests in East Asia because it would relieve the need for extensive American support in the region and support the U.S. Island Chain Strategy — a dated Cold War strategy with a contemporary focus to restrict and control sea access of rivals. This first began with the Soviet Union and has now moved to China by stationing American military garrisons along vital Pacific islands to demonstrate power in the far east and to monitor rivals. Taiwan’s position is strategic and vital to U.S. surveillance, deterrence of a Chinese attack and submarine tracking.

If Taiwan is successful in constructing a “T-Dome,” then the U.S. would gain another powerful ally to deter China, which could benefit Taiwanese military intelligence in the long term.

Finally, the threat of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan is comparable to that of Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, a global superpower intimidating and laying claims to a smaller and sovereign country, but this time, Taiwan can be more prepared than Ukraine.

No one wants to see Taiwan become the Ukraine of Asia or the Ukraine of the east, and this “T-Dome” might just prevent that by creating a precedent for the future expansion of Taiwanese defense. The Trump administration needs to prioritize Taiwan’s plans for a “T-Dome” with Lai’s administration, but also to demonstrate that the U.S. is committed to upholding its promises made in 1979.