What does it mean to be a public university?

It’s not just pursuit of knowledge. Although it plays a crucial role, desire of knowledge is something that all colleges seek to foster, be they public or private. Research isn’t a necessary condition either. For some public universities, it’s part of their mandate (like the UC), yet others don’t necessarily do research (like the CSU system); either way, they are still universities. And much to the surprise of many of us first-time students, it’s not all booze and parties either.

It’s something a lot more foundational than that — and a lot simpler. At the end of the day, a public university is just an investment by a society in its collective future. Essentially, it’s a trade-off. We as taxpayers decide to give up a little bit of our present income. In return, our institutes of higher learning, funded by our dollars, work to benefit our future society, one where we have discovered the cure for malaria, prevented the warming of the globe and educated citizens who can then become hard-working, productive members of society.

California citizens and the state legislators should do well to remember this agreement — especially with the announcement that UC Berkeley has decided to boost its number of out-of-state students solely to raise revenue. In the past, Berkeley set a target for out-of-state students at 20 percent. But now, facing the tightening budget vicegrip, Berkeley has boosted it to 23 percent.

“In the wake of the state’s disinvestment in higher education, UC Berkeley’s financial model is more dependent on tuition than it has been in the past,” UC Berkeley Chancellor Nicholas Dirks admits. Without the financial support from the state, Dirks can only say that the decision “was the best available option to help minimize the campus’ ongoing operating deficits.”

Let’s first point out that accepting more out-of-state students is not inherently a bad thing. Out-of-state students provide any university with a breath of fresh air. Universities recruiting the same students from the same locations for too long results in a stifling of creativity and a stagnation of ideas. Critical thinking atrophies as students aren’t forced to challenge their norms, counter to the UC’s very existence, which serves to expand horizons, not close them. Out-of-state students are like a spring breeze after a cold, still winter, bringing with them different ideas, cultures, identities and beliefs. Dialogue is refreshed and the bud of knowledge is renewed. Without having out-of-state students as part of the university experience, UC life would be stale.

This is the rationale often presented to California students when the UC debates increasing its out-of-state admissions. Now we know that it is all a ruse — the desire for more money is just too much. Somewhere, buried under a need to satiate its hunger for more funding, that original goal of promoting diversity of opinion may still hold true. But it’s been swallowed by a neverending, single-minded obsession over money. The UC’s reasons for pursuing actions are just as important as the actions themselves. The decision to admit more out-of-state students isn’t inherently wrong. But the futile attempt at justification (We can’t help it, we need the money!) is pitiful.

The admission is disappointing, but unfortunately it’s also hardly unexpected. After all, it is a rational decision in turbulent economic times, and UCs have to do something to make up the difference in funding. Should they refuse professors tenure? Roll back academic services? Deny hard-working employees a cost-of-living increase? It’s like a hungry child having to choose between eating prunes and brussels sprouts. The UC is not wanting for choices — there’s a buffet of them on the table. But all of them induce the gag reflex at best and are inedible at worst.

The most disconcerting aspect of UC Berkeley’s new policy is the reason for the new policy existing in the first place: the state’s divestment from higher education. More than anything, UC Berkeley’s move reflects a new reality where the state no longer takes heed of the basic contract between its people and its future.

The entire idea of a public university requires the state to financially support it. Failing to do so does not mean the university no longer needs funds. Instead, once-proud institutes of higher education degenerate into slavish courting of wealthy donors and institute merciless tuition hikes. The result is a concentration of power among an oligarchy of cash-infused tycoons who can grant the university money — but only at their capricious whims. Meanwhile, students are shouldered with the cross of providing our society’s future benefits. Such a state of affairs leads to corruption in academia, a decrease in social mobility and a failure of society to preserve its future.

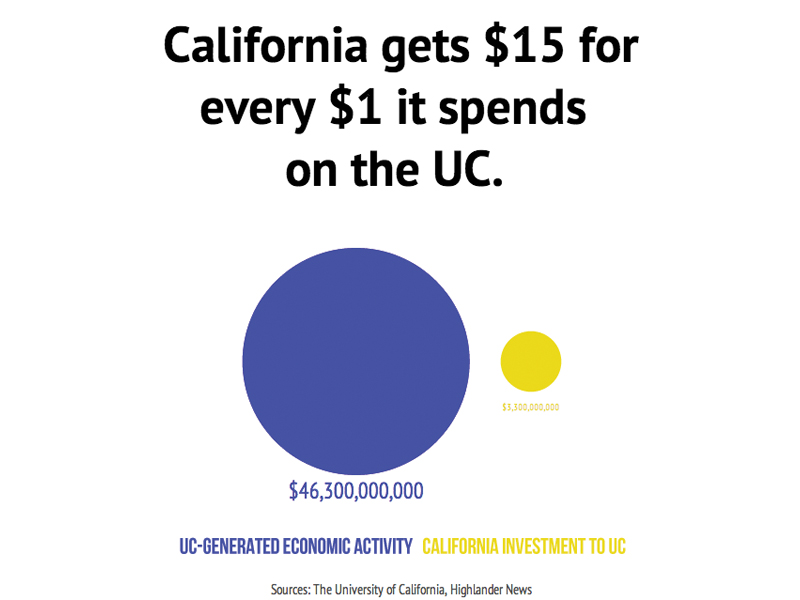

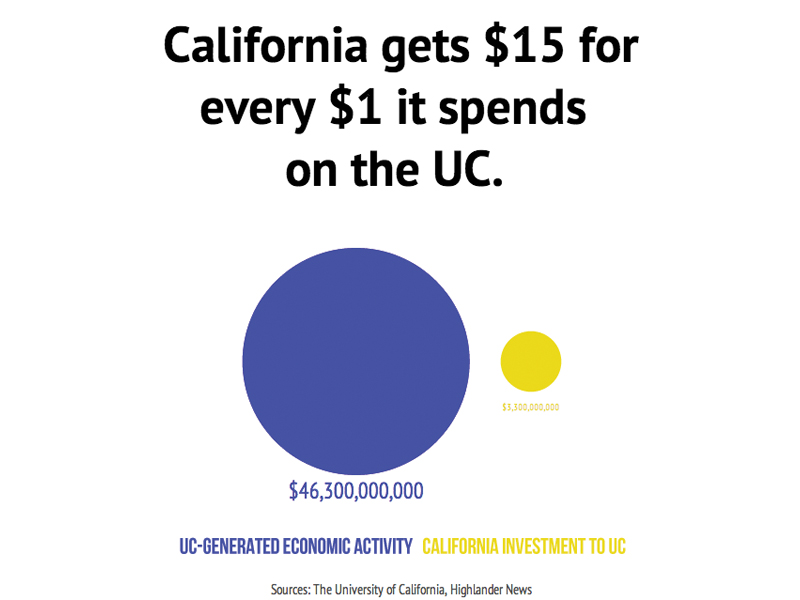

The UC provides the state with $46.3 billion in economic activity every year, a more than 15:1 return-on-investment. UCR alone provides the state of California with over 13,000 jobs and more than $1 billion in economic activity. Four of the top five universities that contribute to the public good are UCs, providing California with countless intangible societal benefits that the state would go without otherwise. This seems like a more than worthy deal for the state of California.

As we consider UC Berkeley’s decision to prioritize grabbing funding over educating students, it’s just as important to look back on why this is necessary in the first place. For more than a century, our society’s basic bargain has been upheld. The state grants the university public money. The university gives the state future growth. The UC has upheld its end of the deal. Now it’s time for the state to do the same.