“Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me.”

This proverb is especially true with “microaggressions,” which Derald Wing Sue, Ph.D, defines as “everyday verbal, nonverbal and environmental slights, snubs and insults,” based on one’s race, sex, class, etc. Many institutions, like Clark University, go so far as to hold presentations cautioning students against using microaggressions, lest they offend anyone they meet. While respectful social conduct is important, pestering students to scrutinize every single sentence for these tiny barbs leaves everyone walking on eggshells for fear of offending others and reduces the gravity of actual cases of racism and sexism.

One issue with the concept of microaggressions is that it attempts to reduce every social interaction into a clash of biases. A theoretical example is a non-Asian student asking an Asian student for help with math homework. A hunter of microaggressions might condemn the non-Asian student for assuming that Asians are inherently experts at math based on stereotypes. That could be the case in this hypothetical situation, but real-life interactions are far more complex and have many more factors that have nothing to do with racial bias.

In reality, one student might ask another for math help for a number of valid reasons. They could both be in the same math class, or maybe the Asian student took that class in a previous quarter, or maybe the students are just good friends who help one another out with homework from time to time. There’s no need to dissect every social interaction on the hunt for covert racism if there is no evidence of it.

It’s particularly damning that most of the witch hunt for microaggressions is based upon the interpretations of remarks and actions, rather than the facts of the situation. At Clark University’s presentation, the phrase “you guys” was identified as a microaggression because it could be “interpreted” as excluding those who don’t identify as “guys.” The operative word here is “interpreted.” I can interpret someone telling me, “Nice glasses,” as “Nice glasses, four-eyes!” but that doesn’t mean they were insulting me. Chances are, it was just a compliment. Living with constant vigilance of “subtle” racism and sexism lurking around every corner is similar to living with a persecution complex. It’s an easy way of making yourself miserable and paranoid.

If we’re going to start taking offense at the term “you guys,” then where does it end? In Spanish and French, the proper grammar for referring to a group of mixed gender is the masculine term: “ellos” for Spanish and “ils” for French. Oh, the nerve of those Spanish-speaking and French-speaking countries, always finding new ways to grammatically oppress people!

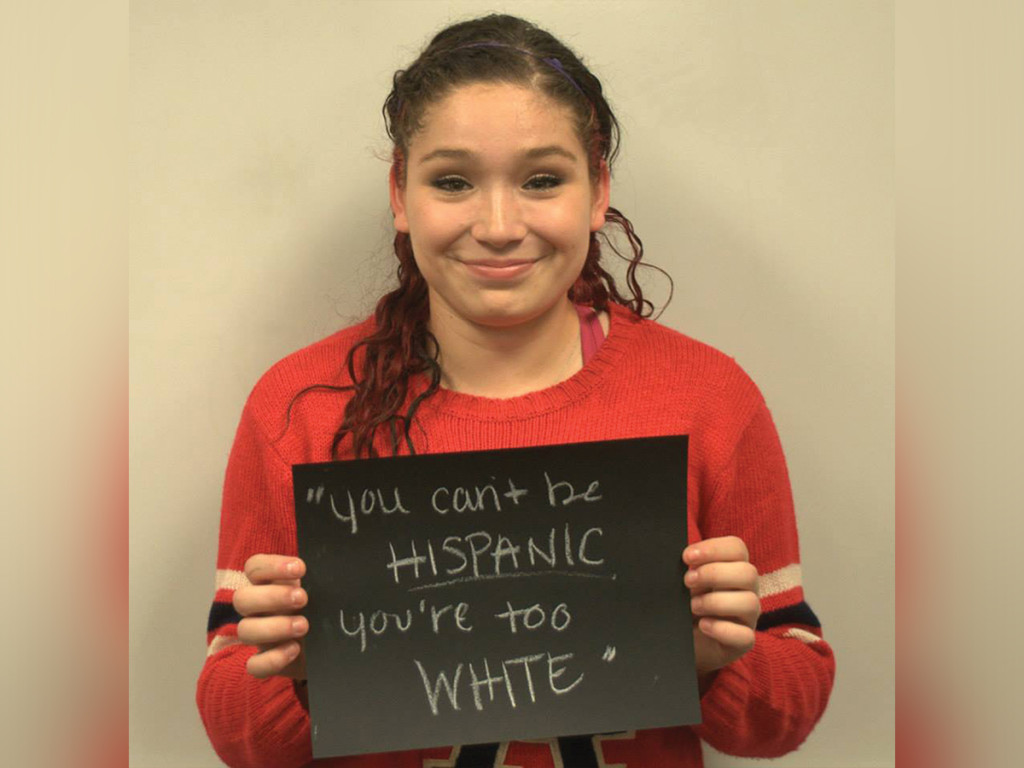

When we use the excuse of “stopping microaggressions” to constantly throw the racist, sexist and all the -phobic labels onto otherwise innocuous interactions, we desensitize others to the realities of actual racism and sexism. Telling a black student, “You’re really smart for a black person,” is a legitimately racist comment, and should be called out. Telling a female chemist, “Wow, I didn’t think a woman could do well in this field,” is a legitimately sexist comment, and should be called out. But those comments aren’t microaggressions, because they have explicit evidence of racism and sexism in them. When we label every little remark as some kind of -ism or -phobia, we lessen the impact that those labels have, and people become apathetic to the real issues.

Microaggressions are a non-problem. People who choose to pore over every interaction and social nuance for minute traces of racism or sexism are wasting their time. If someone is blatantly abusive, insulting or discriminatory, you should tell them to stop. But living in fear that insults, taunts and biases are hidden under every harmless and banal interaction is no way to live. It’s a quick way to stress yourself out, and it creates more problems than it solves.