Love movies? Want to expand your movie-viewing toolbox to elaborate on why you love them so much? With “Reading Film 101,” we take great scenes from film and unpack them to better understand the magic that goes into the art of film.

There’s a fascination with the scenic American idyll that pervades the whole of David Lynch’s oeuvre. Specifically, Lynch loves to erode the myth of American exceptionalism through horrific penetrations of small-town settings brimming with hope, as well as violent suburbs masquerading as safe havens. “Blue Velvet,” which polarized critics when it released in 1986, lays forth this thesis of subdermal violence beneath the pretence of quaint peacefulness in its two-minute opening scene.

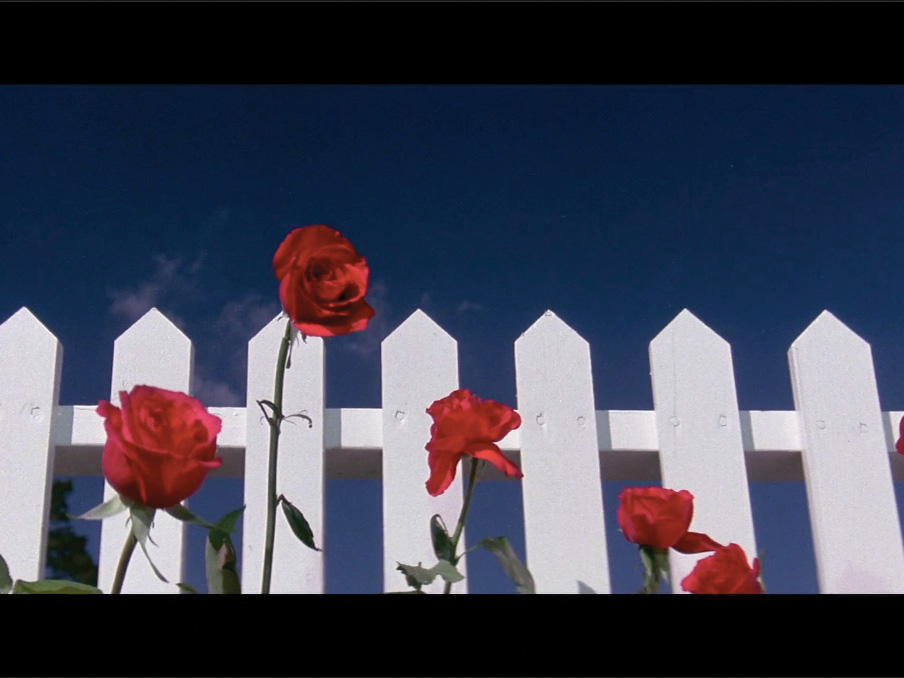

The title of the film owes itself to Bobby Vinton’s 1963 rendition of Bernie Wayne and Lee Morris’s “Blue Velvet,” the track appearing in its opening shot. “There was something mysterious about it. It made me think about … lawns and the neighborhood,” Lynch expresses in Chris Rodley’s extensive interview book, “Lynch on Lynch.” Those lawns and neighborhoods actualized in the film’s suburbs of Lumberton: A clear blue sky overlooks a white picket fence adorned with luscious red roses.

Of note is the heavily saturated color grade that makes the roses pop against the white fence, a beautiful lawn if there ever was one. The low-angle shot helps establish the feeling that something — something small, indescribable even — is off.

As the song continues to play in the background, a dissolve presents a firetruck strolling by in an eerie slow-motion shot. A man stands stiff as a corpse, waving, beside the stereotypical fireman’s Dalmation. Not only is the setting pretty, but safe, too — a welcoming public servant lets us know that all is well. Another dissolve tells us that kids are safe here too, crossing the street with the help of an elderly crossing guard and the sky is coated with a sky the shade of cotton candy pink. In case the message wasn’t clear: Things are nice here.

All these images are in service of a dream-turned nightmare, the disruption of the peaceful familial suburbs. The nostalgia lasts briefly before the darkness creeps in. While watering the lawn, a man suffers a stroke. The man is Jeffrey Beaumont’s (Kyle MacLachlan) father, and his stroke shifts the trajectory of the opening sequence from picturesque to macabre. The music, still playing, juxtaposes the scene to layer the unpleasantry while a dog licks from the still-spraying hose shooting upwards and a toddler, unaware of what just happened, walks idly by.

The opening sequence is punctuated by a careful zoom-in toward and through the blades of grass, infiltrating the deepest recesses of the lawn. The music is gone, replaced by a horrific humming that drones on as the camera pushes closer. Beetles intermingle with another, as black as they come, with the sounds of their bodies moving around amalgamating to a cacophonous crunching and crinkling. It’s a grotesque couple of shots that quickly cut to a sign of the town: Welcome to Lumberton! Home of pretty lawns and deeply hidden horrors, sponsored by the human subconscious.

It’s always important to consider simple filming elements like non-diegetic music (elements occurring outside the world of the film, as with a score, contrasting with diegetic elements that occur within-film, as with radio) — the song sets things up as pretty, making the climax of the scene so much more unnerving. Dreams play an important part in Lynch’s work too, with the sequence playing out like one; knowing the filmmaker and their intentions helps in understanding the meaning of a work and context is everything.

“Blue Velvet” is a difficult movie to watch, filled with scenes of violence and surrealism that don’t exactly welcome most viewers. But it’s an incredibly effective work, and part of its effectiveness is the attention to detail in scenes like this, with an abundance of nuances that echo its multiple themes, including the puncturing of the ideal. While it is certain to deter many, those who can stomach it will find a classic in American cinema directed by one of the weirdest filmmakers in the mainstream.