To enter into Guillermo Gomez-Pena’s theater is to come to terms with the irrationality of the world. For the last 30 years, the Mexican artist has committed himself to stitching absurdities and contradictions together whether they be past or future, indigenous or contemporary, citizen or illegal, white or color, straight or queer, logical or sensible.

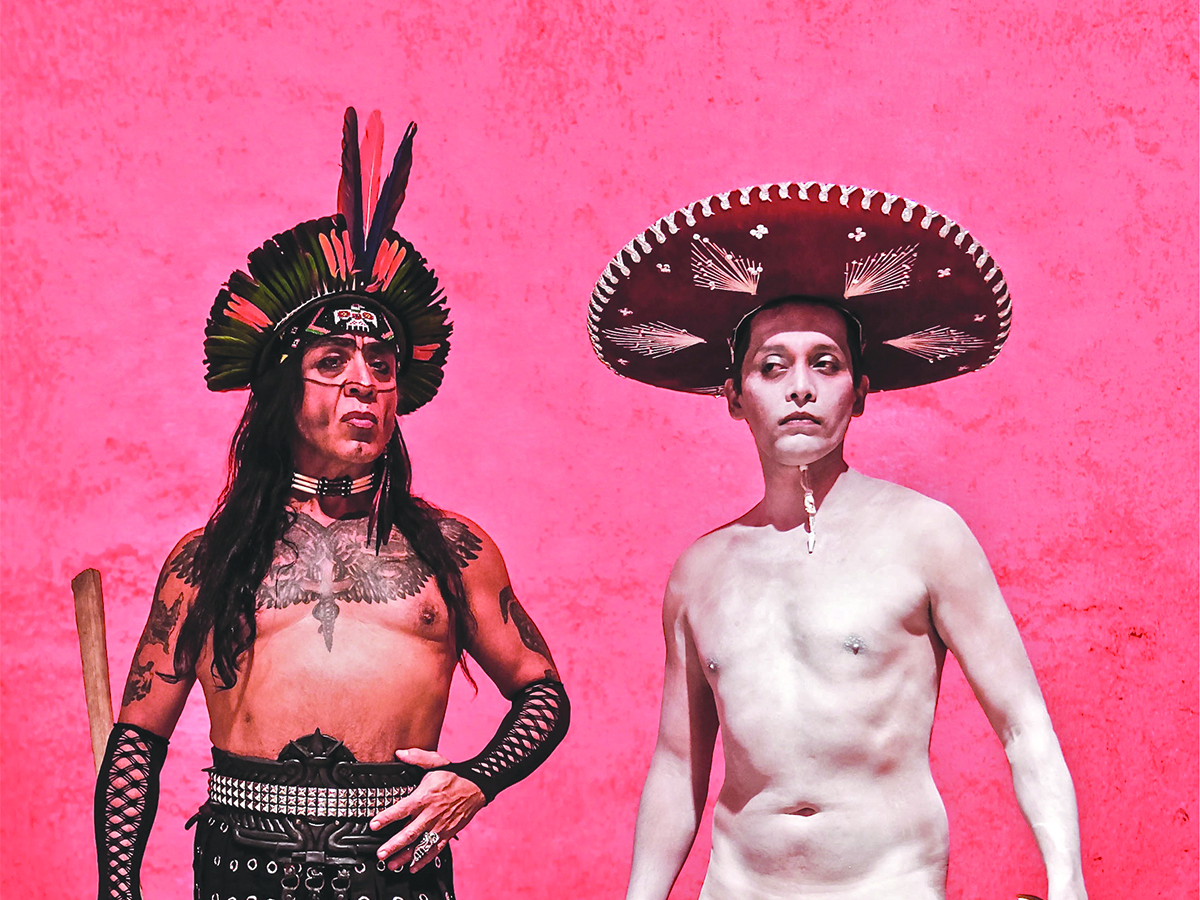

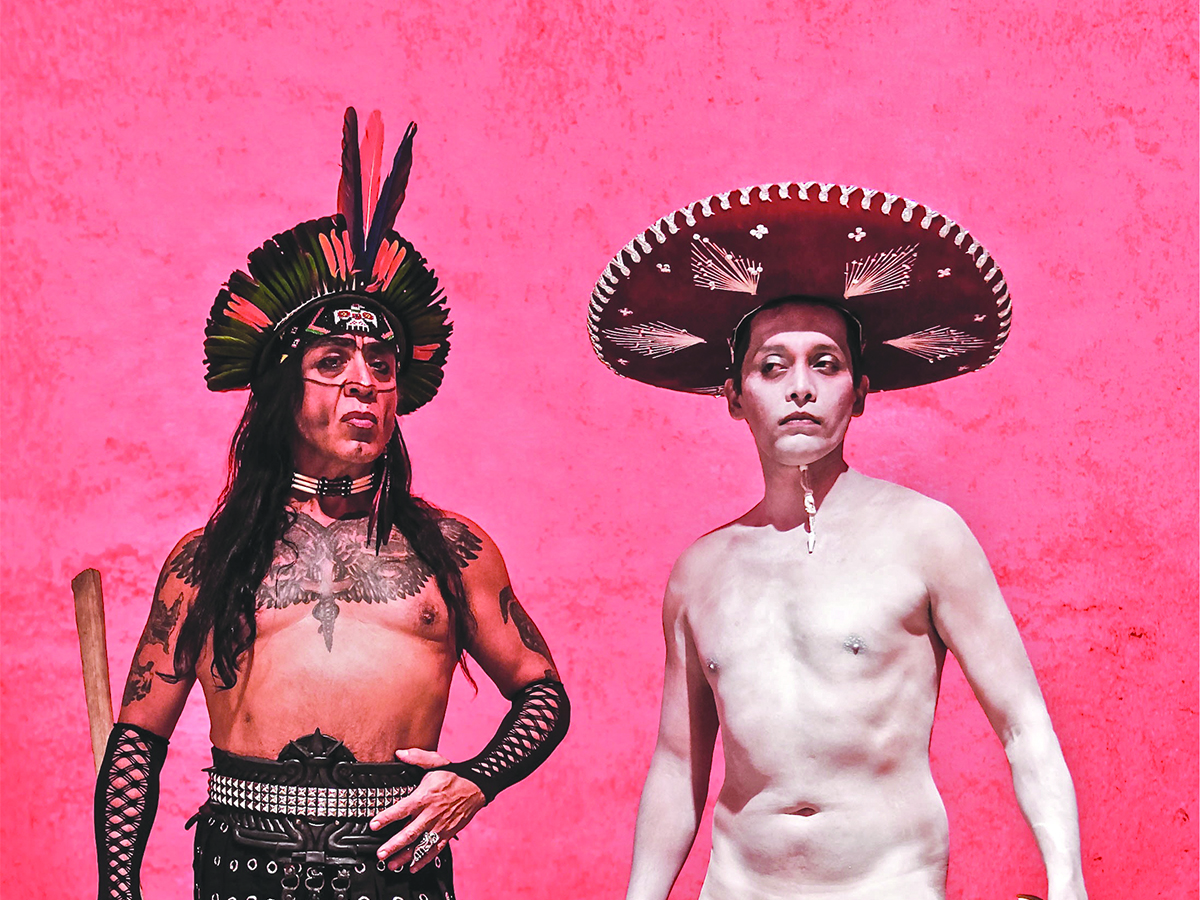

“La Nostalgia,” a photo portraiture series which features the performance cadre La Pocha Nostra, remixes swatches of indigeneity and modernity flavored Latinidad. In one portrait, artist James Luna is adorned in a vibrant red zarape, feathered headdress, beaded accessories and futuristic wide-brim sunglasses, standing alongside a topless Gomez-Pena in a traditional embroidered corte skirt. These are portraits that demand to be studied and savored. Gomez-Pena’s visions of Latinidad are surrealist, bleary, balmy interpretations of the Latinidad’s muddled racial and ethnic history. Gomez tends to use the iconographic as material — traditional Mexican anythings — like saturated images of native peoples, Hollywood depictions of modern Mexico, Latino sentimentality, cowboy regalia and the body itself. His masterpiece with Coco Fusco, “The Couple In The Cage,” — which catapulted Gomez-Pena and Fusco into art world titans — toured two never-before-seen pre-Colombian natives touring the Western world. Peering into “The Cage” offered a preliminary sketch of the body of work Gomez-Pena’s clownish iconoclasm was yet to conjure.

Gomez-Pena, who is 62 years old, is still ever as impish, committed to a stitch work of assumed opposites. His newest work, titled “The Most (un)Documented Artists,” stopped at UC Riverside Artsblock, as part of the Mundos Alternos exhibit. The performance began with a militaristic lining up of the audience by performer Saul Garcia Lopez, who wore nothing but a black mask, black apron and heels. Lopez took people inside one-by-one at first, then lined people up under a random criteria that left the audience in anticipation. The allure coiled for a moment, engendering the possibility for Artsblock to transform into a bathhouse; what waited was something more serene and tender. Balitronica Gomez of La Pocha Nostra was dressed as a nun, offering a washing of the feet as an offering for “the dreamers,” the eleven million undocumented immigrants in the United States. Audience members waited for their feet to be washed, or to watch the profane ritual.

Those chosen by Lopez were seated on a small altar where they viewed a video examining the fragility of the of the US-Mexico border itself. This opening act set up for Gomez-Pena’s main act. After a few opening remarks by curator Kathryn Poindexter and a long registry of Gomez-Pena’s pseudonyms, the titan appeared, carrying a sense of regality and humility that made him endearing. He was dressed in a t-shirt that read “policia,” paired with a long black skirt wedged tightly by a embroidered belt.

Gomez-Pena ran through a series of text performances where his trickery distorted the languages of casual racism, sexism and colonialism, aided by glitchy pronunciations of humor, neologisms, irony, double-entendre and innuendo. At moments, it mirrored comedy formats of network skit shows. Perhaps the name of the show can be Vato TV.

In one sketch, he returns home to his Macbook “XY-Lion-24,” waiting for his touch after Gomez-Pena’s perilous tour. The two begin to engage in sex where they eventually climax and enter the computer’s motherboard. Gomez’s computer dirty talk is nothing but lewdly hilarious in contrast to the machine’s slow annunciation “g-o! f-or! It! Go-mez!,” a slanted giggle at white American pronunciation of anything slightly tinged in Spanish.

The machine’s slow and restrained annunciation (voiced by Gomez) kept at bay a source of pure emotion underneath its mechanic shell. In one moment he tells the machine, “You’re in the process of Mexicanization.” It’s a climax which causes the computer to freeze and forces it be rebooted. The computer begins to make white noise reminiscent of Daffy Duck, to which Gomez-Pena responds, “That’s what English sounded to me in the beginning.” It’s as if his cyber romance was nothing but his own holographic musings. his isolation just a toy to entertain. It’s reminiscent of the cyber erotica “Her,” where protagonist Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix) is devastated by his AI lover’s global polyamorous affairs. Often in science fiction films like “Her,” the future is built on the internal isolation of the protagonist that is color blind to the racial and gendered dynamics that shape the film. Gomez-Pena’s loneliness is not that of schmaltzy pity but rather a dirty joke shared among the many persona’s of Gomez-Pena.

Gomez-Pena’s future is a future that oscillates between the utopian and dystopian. It’s skyline is garrish, vast, rapid, intrepid, jarring and wacky, almost nihilistic. At the same time, he’s too entrenched between an optimism that confluences his slippery and evanescent collages of history, Latinidad and clunky cybernetics. Upon leaving the performance, in his world, there was a collective uncertainty whether the monologue was for the audience or if it was just a glitch in Gomez-Pena’s wired mind.