“It don’t take long to kill things. Not like it does to grow.” These are the words that Homer Bannon (Melvyn Douglas) utters after he witnesses a brutal execution of his hard-earned livestock in the 1963 film “Hud.” Life is slow on his Texan ranch, with work and casual leisure being all the surrounding town and its inhabitants have to offer. Hud Bannon, however, cannot let his environment dictate him; he gets what he wants, letting nothing, especially his father, stand in his way. Homer’s grandson Lonnie (Brandon deWilde) takes a liking to his Uncle Hud, and it soon becomes apparent that the barrenness of the countryside will prove a fitting setting for the titular character. Familial, moral and economic strife are juxtaposed without awkwardness, culminating in a tale run by an unbounded sense of grounded realism.

Based on the prolific author Larry McMurtry’s first novel “Horseman, Pass By,” director Martin Ritt captures the naturalistic ethos of his prose. However, Ritt changes quite an important detail from the book, making the protagonist Hud, not Lonnie. A stark contrast to the traditional, simple duality of man in conventional Westerns, Hud’s character distinctly blurs these lines, affirming his status as an anti-hero. Being a charismatic and suave individual, the common mistake of assuming him to be the “handsome leading man” throws an atypical spin on the narrative. The audience grasps for reasons to understand Hud’s destructive behavior, but his pretty boy persona can only mask his malice temporarily. It becomes harder to forgive Hud’s trespasses, as he begins to prey on the innocent.

Screenwriters Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank Jr. use Hud’s interactions with Lonnie to enrich the characters and force the audience to experience the events through the latter’s perspective, a choice that calls back to the source material. The pacing is executed in a refined and dignified manner, taking its time to flesh out the subtlest of interactions. Picking up a deserved seven Academy Award nominations and eventually winning three, the components of the work ebb and flow with grace, resulting in a masterpiece on all fronts.

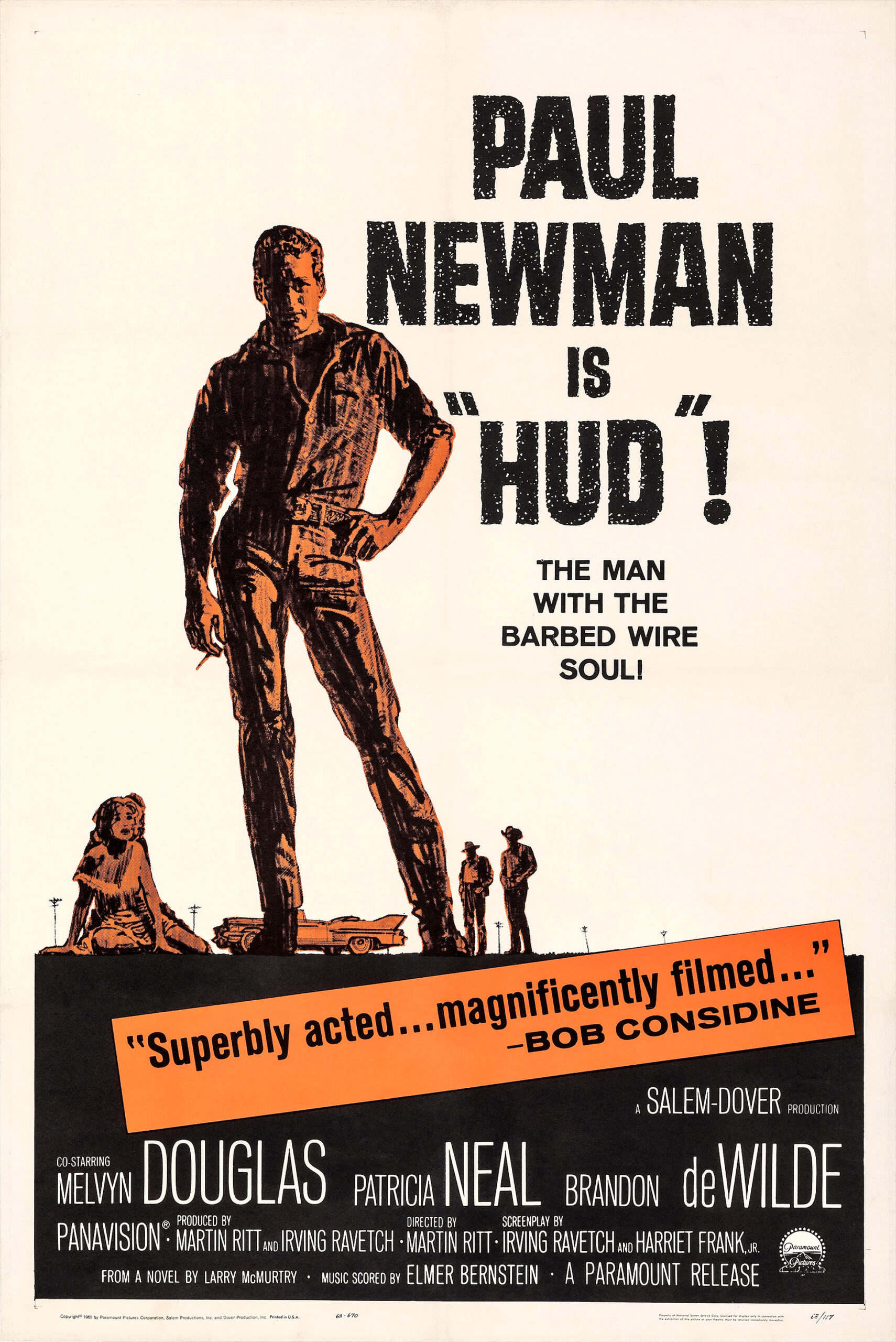

Dubbed “the man with the barbed wire soul” from the film’s tagline, Newman delivers an electrifying, confrontational performance as Hud that riffs off the rest of the cast. His ruthlessness and complete incapacity for empathy are best displayed through his pursuit of Alma (Patricia Neal). His heinous acts toward her are byproducts of his skewed lack of morality, while his relationship with Homer depicts the outwardly cruel yet calculated disregard for respect or responsibility. By not depicting Hud as a one-dimensional person driven only by evil, seeds of doubt are simultaneously sewn into the viewer and Lonnie’s mind. Newman’s expressions begin to force the truth out of those around him, making way for a wide range of complex emotions to be communicated across the board.

Each actor demonstrates a varied component of the effects our interactions have on one another. Impressionable and idealistic at first, Lonnie represents the optimistic new generation, eager to fight for what’s right. Homer’s wisdom is incomplete without learning from the many painful failures undergone in life. This generational gap provides us with the different philosophies each character holds, with their eventual unraveling leading them on the same path.

Elmer Bernstein’s repetitive guitar-led soundtrack insistently rings in our ears, serving as a harsh reminder of how some are destined to never change. This musical presence combined with the conclusion of a dialogue-driven scene is commonly used as a transition throughout. The contemplative nature of this pairing is notably used in works that employ a similar template, with British auteur Mike Leigh’s 1993 film “Naked” starring a similar anti-hero-like, intensely distinct performance from David Thewlis.

James Wong Howe’s cinematography is mainly responsible for the creating atmospheric dichotomy that parallels the muddled disposition of dreariness to Hud’s identity. Shadows are utilized specifically to create the sense of impending doom that presents itself where he goes. This is complemented by the calculated contrast created by black and white photography, which ultimately acts to showcase the ambivalence of human nature.

Our species is driven by demand, and command must be exerted above all those inferior. In Hud’s case, the gifts of intelligence bestowed upon us should only be used for personal gain — only the strong deserve to survive, even if it means being alone. As he says: “Well, I’ve always thought the law was meant to be interpreted in a lenient manner. Sometimes I lean one way and sometimes I lean the other.” It is up to the audiences to decide what we believe is right and to set our standards. The inevitably of sticking to our principles comes with its consequences, proving that the fundamental complexions of our souls ultimately remain undiluted by external forces, no matter how powerful.