The University of California, Riverside’s School of Medicine had its inaugural Ground Rounds event on Apr. 4, 2024, which discussed the history of the current opioid crisis, problems with the current solutions of medicating substance use and possible solutions and perspectives for the issues surrounding drug addiction. The event was the first Dean’s Seminar Series hosted by the School of Medicine’s (SOM) Dean, Dr. Deborah Deas. The seminar was scheduled from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m.; however, the presentation started late due to the speaker, Dr. Helena Hansen, being stuck in traffic. Dr. Hansen presented virtually on Zoom in her car, where she pulled over to give the lecture. The talk was broadcast to the SOM lecture hall.

Dr. Deas gave an extensive and honorable introduction to recognize the notable work and progress that Dr. Hansen has achieved over her career. Dr. Deas describes Dr. Hansen as a “distinguished psychiatrist, anthropologist, and a prominent figure in the field of Social Medicine” and that she “is known for her advocacy of integrating regular social science into medical practice and research.”

Dr. Hansen is a Professor and the Interim Chair of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences at the University of California Los Angeles’s (UCLA) David Geffen School of Medicine, and Interim Director of the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior. She has written numerous published articles and three books to change the lens of how medical practices and research seek to cure substance use. She is also involved in various governing boards to facilitate the advances in health care and advances in solutions for social issues. Dr. Deas marks her as a “trailblazer” within her field.

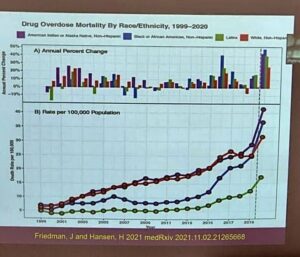

Flattered by the introduction, Dr. Hansen begins her presentation which was centered around her latest book, “Whiteout: How Racial Capitalism Changed the Color of Opioids in America.” She starts her presentation by introducing a JAMA Psychiatry published graph (figure 1) from 2020 to solidify that overdose affects all ethnic groups. In the graph, Native Americans were shown to be overdosing at higher rates than other ethnic groups, to which she points out that overdosing is no longer the “white crisis” it was once portrayed as.

Next, she describes the different waves of overdoses since the late 1990s and how they affected different ethnic groups. She states that “Black and Native Americans were disproportionately exposed to fentanyl [because] the more socially marginalized consumers of street supplies had less control over the content of those supplies.”

She vocalizes that for people who are released from jail or prison, the risk of relapse is incredibly high, and their tolerance to opioids is very low. Furthermore, they are disqualified from many public benefits due to their criminal record, which feeds into a “vicious circle of mass incarceration.”

Dr. Hansen continues to explain that Black and Brown American deaths from street supplies of stimulants and fentanyl are originally derived from, a term she calls, “technologies of whiteness” that were once used to promote prescribed opioids. She explores solutions and problems centered on the opioid epidemic by studying the mechanisms of whiteness, instead of “looking at the problems within the Black and Brown communities.” More specifically, she goes into detail on the white-exclusive opportunities in medicine as the cause of health disparities among underserved minority groups, which may lack access to care.

PC: Alexandra Arcenas / The Highlander

Thus, she explains that the white racial identity is “central to our environment of profit motives, commodification, and open pharmaceutical markets.” Therefore, it may lead to pharmaceutically enhancing the whiteness of people whose privilege is in jeopardy due to the stigma of addiction diagnoses. She introduced drugs such as Buprenorphine, a synthetic opioid used to remedy pain and opioid use disorder, as an example because it was marketed to change the culture of medicine and would treat addiction like any other chronic disease like hypertension or asthma. However, Dr. Hansen exposes the fact that during the same time, the racially targeted drug war policies led to the persecution of Black and Latinx Americans. Therefore, putting the United States in the lead for the highest incarceration rate in the world.

Dr. Hansen continues to explain the logic and reason behind the racial disparities in opioid treatment in hopes of educating and advocating for more social intervention accompanied by medication and medical practices. She calls for leveraging technology to address social determinants of health. Dr. Hansen also stresses not only treating the addictions themselves but also managing the pain that may have been the cause of substance use. Dr. Hansen believes addiction treatment should be approached with multidisciplinary care and urges others to look at addiction and drug use with less stigmatizing perspectives to develop a solution for substance use disorder.