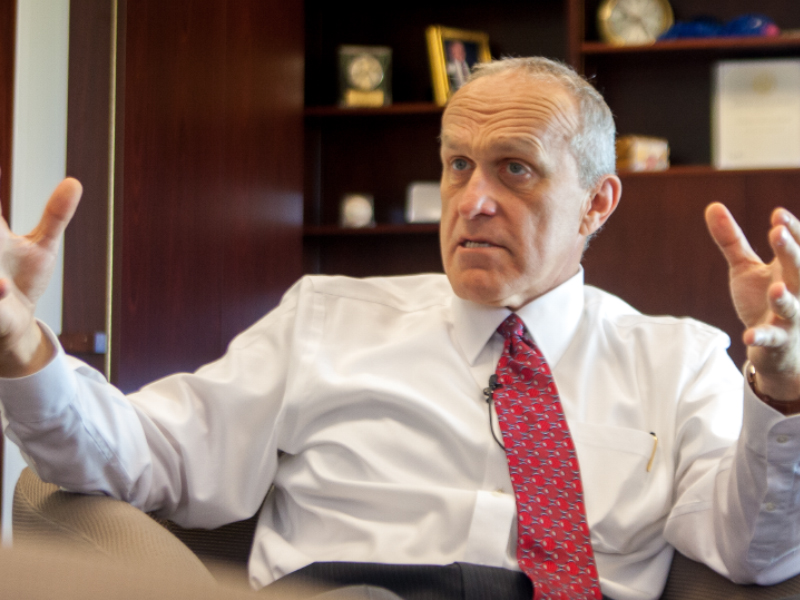

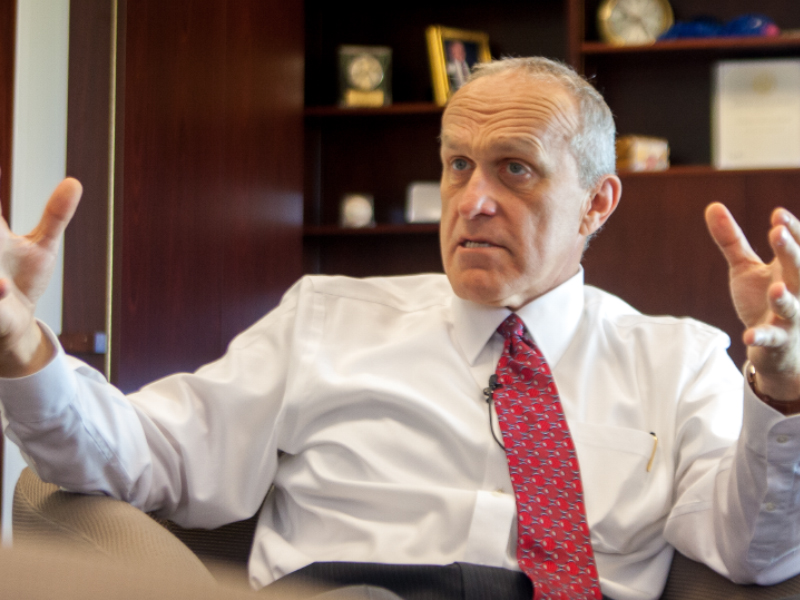

In my first time inside the chancellor’s office, I sat directly across from Kim Wilcox, whose feet lay propped up on another chair. We sat at the conference room table in his office, a place he spends the majority of his day. Discovering what the chancellor eats for breakfast instead of plans for next year’s budget, I caught a glimpse of the reality of being UCR’s ninth chancellor. “When someone opens the door, you’re not the chancellor of UC Riverside anymore. I am. Teach me how to be chancellor,” I said. Wilcox gasped, “Oh — whoa,” as if I broke the news that the president was just impeached.

“Let me go to first principles,” he said. He admitted that — in his opinion — the principles of an ideal chancellor had more to do with the office than with Riverside in particular. “I believe jobs like this require some things. They first require someone to be a very good listener. You have to be an active and respectful listener … always trying to tie things together.” He then added that he regularly reminds himself that most people don’t get to walk into the chancellor’s office, whereas he is in it everyday.

I was squeezed into the chancellor’s schedule just 20 minutes prior to his next meeting. In fact, it was a timeslot that had been rescheduled three times prior. The chancellor’s schedule, especially Wilcox’s, does not include gaps for leisure time or, for that matter, much downtime at all.

“You have to be ready to release control,” he said. “I don’t create my schedule, Suzette does.” Suzette, the chancellor’s assistant, hands Wilcox his schedule every evening so he knows where and when to be for the next day. Expressing his preference for distancing himself from the details of the scheduling process, Wilcox further noted that, as chancellor, one must feel comfortable with having somebody else schedule their life.

What makes Wilcox even remotely comfortable with this notion is not his lack of interest in scheduling but rather his dedication to creating “a team of people that feel like a team.” Wilcox sees the importance of a close team as not just important to himself but for the whole campus. He related, “You have to be in an environment where people feel confident that when the vice chancellor for student affairs speaks, he’s speaking with the support of the chancellor. If that isn’t believed, then the whole system doesn’t work. For that to truly be the case he has to feel and I have to feel it.”

On a typical day, Wilcox wakes up at 6 a.m. at the chancellor’s residence on Watkins Drive and is on his treadmill by 6:05 a.m. for “three 10-minute miles — no faster, no slower, that’s it.” Wilcox wraps up his morning workout with 20 pushups and 80 situps — although he did disappointedly admit he had not been able to do all 80 situps because of a strain in his back. He then joked that he’d given me more information then I asked for, only to follow with his renowned hearty laughter, which could fill a room the size of University Lecture Hall.

After reading the newspaper with a breakfast of yogurt and fruit, by a quarter to eight, Wilcox is in his office on the top floor of Hinderaker Hall. He describes the majority of his day as meetings held at the very table we spoke at — the table that Wilcox complained about being too low because his knees hit the top.

Yogurt, cheese sticks, crackers and fruit fills his desk when it is time for lunch, with a Diet Pepsi to complete the hearty meal. “Living large,” he joked. I could not help but smile as I envisioned Wilcox, like Tom Hanks’ airport-stranded character in “The Terminal,” carefully preparing and taking great delight in a sandwich of saltine crackers and cheese sticks. Noticing my reaction at his rather average routine, Wilcox acknowledged that it isn’t “the glorious life you may think. But it’s great fun.”

For the chancellor, great fun is not much different from average students. The chancellor has the opportunity, on a daily basis, to engage with and learn from a variety of unique and interesting people. The only difference is he has only as much as an hour to make a meeting count — and that’s it. He has to do his best then to move on to the next meeting on his schedule and know he made the most of it and if required, the best decision possible. To be chancellor is to be “in the moment” and feel comfortable engaging in the next topic despite knowing he might have done better if he spent all day on it — however, for Wilcox, “that’s not an option.”

For many people, just the hint of taking on more than one project at a time is horrifying. Some people think academics have become academics to have a low-risk, low-pressure environment where they can focus on their own interest of study. Wilcox, however, is anything but horrified by his new reality as chancellor. Somewhere in his gut there is a feeling — a feeling to not just make a difference but a lasting one.

Wilcox’s overarching advice, in serving in the role of chancellor, is something like this: It is easy to be liked by everyone by not doing much. If he wanted to — and he says some people do — Wilcox could not do much and get away with it. He acknowledged that if “you just go to events, have fun, eat cookies, give speeches … everybody will love you.” Knowing this to be unfair to the campus, he further proclaims that it is his obligation to do things that are not fun and will even make people very upset — even if they are the right things to do. Wilcox, as he often does, shares a story of his mother, who was a secretary her whole career. He says his mother would often come home frustrated and say, “I don’t know why they don’t do something about that.” Wilcox acknowledges that he is now “they.”

As “they,” Wilcox describes his job as leaving the campus “a whole lot better” than when he arrived and frequently asking himself the question: “What will this mean 20 years from now?” He realized, “That’s the other guiding principle in all of this. You have to keep your eye on the longer term prize.” Then the door knocked. It was time for his next meeting.