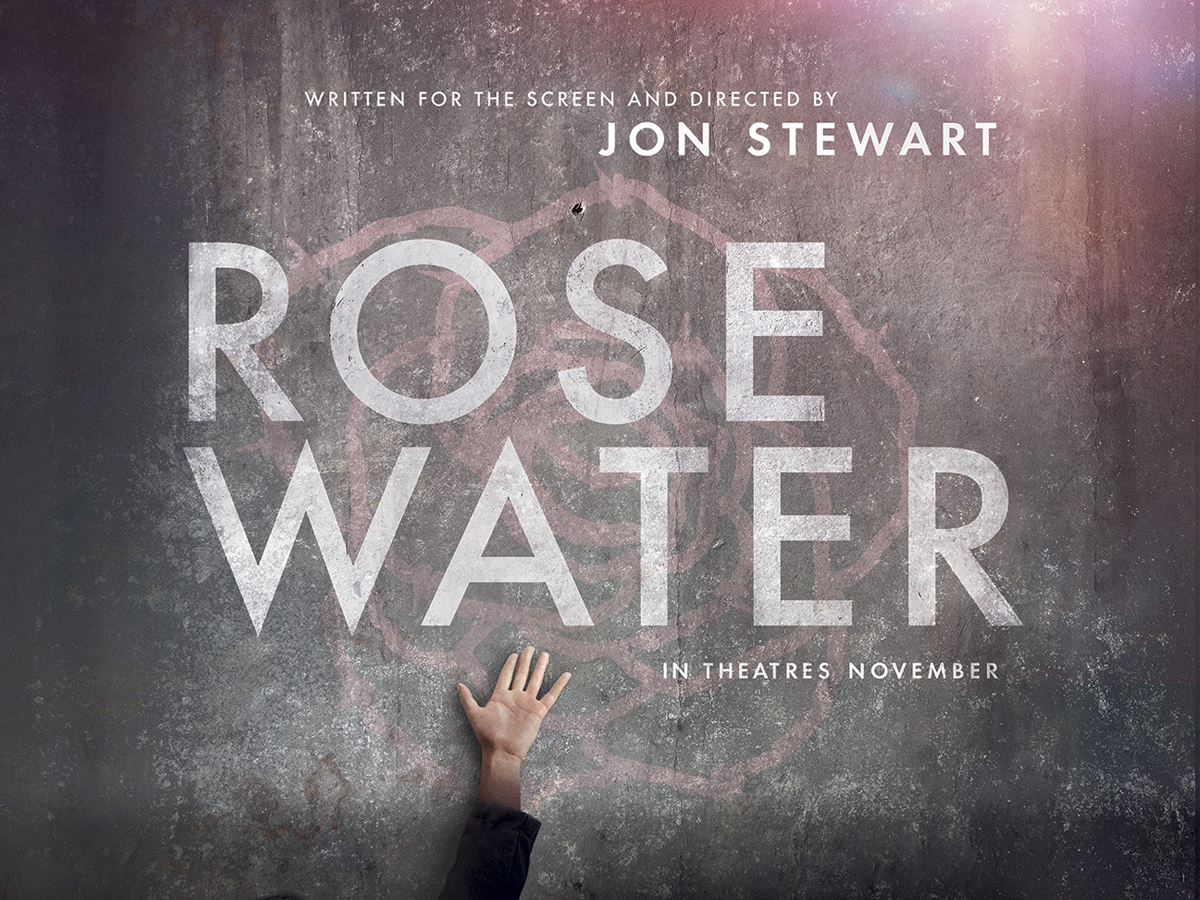

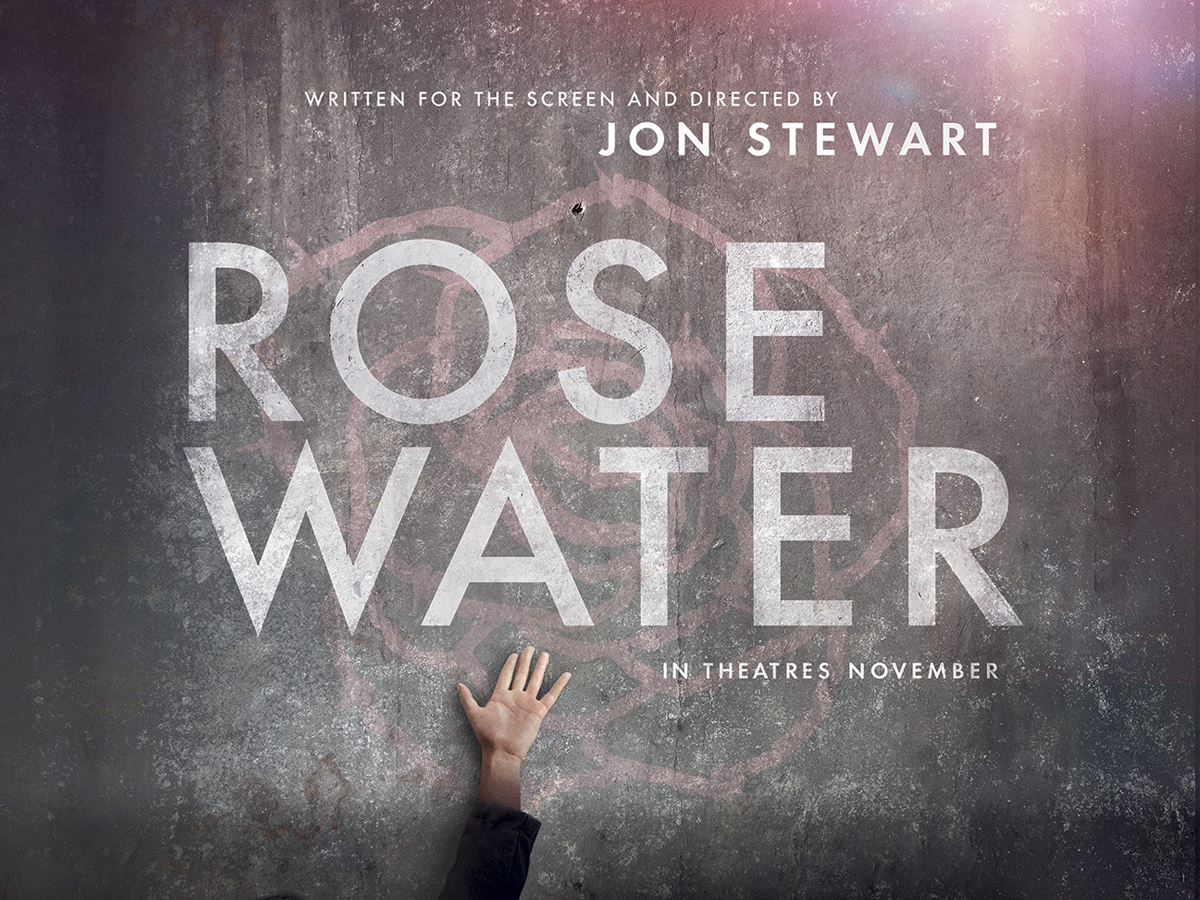

While he is an amazing satirist in front of the camera with expressive hand gestures and funny rants, Jon Stewart is a tad awkward as a director in his first movie, “Rosewater.” Based on Mazier Bahari’s imprisonment in an Iranian government’s jail for being an alleged spy, the film accomplishes its main goal — discussing the need to protect journalists against government oppression — yet the editing and writing flops around this blunt theme. However, redeeming it are the gripping characters, specifically the grueling yet humorous interrogation scenes between Bahari (Gael Garcia Bernal) and his nameless interrogator (Kim Bodnia) — known for wearing Rosewater perfume.

For the first half of the film, the story sets a steady, but routine, pace with scenes concentrating on the tensions surrounding the 2009 Iranian presidential election, building up to Bahari’s forced confession on national Iranian television. These tensions are enhanced by combining real footage of the protests, the presidential debate and international news coverage, such as when Bahari wills himself to film protesters being shot. The scenes smoothly transition between the film and Bahari’s actual footage of the shooting, giving the necessary essence of reality to this highly political film.

However, “Rosewater” is not just about politics — it’s about Bahari. The growth and exploration of his character often refers back to his childhood, when his father and sister also underwent imprisonment. While a bit cliched (but necessary), the ghost of his father allows Bahari to confront his troubled past and present through dialogue with the dead, but these scenes usually zoom in and out with his ghost father appearing and disappearing beside his son. It is a healthy reminder from the film to the audience that the father is a figment of Bahari’s imagination. And it is unnecessary — the editing, not the father.

His sister Maryam exists in flashbacks introduced in flashes of searing white or in other brief moments to comfort her younger brother in her popped-up ghost form. Even Bahari’s ultimate realization, that there is an international effort to free him, is expressed through a montage of various 2009 news coverage discussing his imprisonment that Bahari somehow envisions: Paola Bahari, his wife, stands, timely emphasizing the need for him to have hope by holding her pregnancy bump, in front of a green screen presenting more news coverage as if she was the weather forecaster no one listens to. Somehow understanding he should never relinquish hope in a montage edited like a news channel, Bahari presses on.

All the awkward editing aside, the acting offers vitality to Stewart’s statement that, “We hear so much about the banality of evil, but so little about the stupidity of evil.” Instead of implying that all of the interrogations between Bahari and Rosewater were just beatings, name-callings, death threats and questionings of his sexual background, Stewart does justice to the journalist’s belief that his imprisonment “was stupid and funny at the same time.” Rosewater constantly cross-examines Bahari with questions that are earnest and genuine to the interrogator, but are actually rather silly. During their first scenes, Rosewater pointedly asks, “Who is Anton Chekhov? … You tell me. It is you who has listed an interest of him on Facebook.”

Once Bahari revitalizes his hope, he teases Rosewater with titillating lies of traveling to sexual massage establishments all over the world as a somber confession of his disloyalty to his wife. When Rosewater is astounded that Fort Lee, an American army base, is the infamous destination for massages that can cause men to die of pleasure, Bahari softly laughs, which encourages the audience to laugh out loud. His Napoleon Dynamite dance routine in his solitary confinement cell celebrates not only Maryam, but “the stupidity of evil” as the dance routine scene contrastingly switches to a dark, silent room with Rosewater confusedly looking at a monitor of Bahari dancing to no music. This was editing and composition done right.

Clumsy, dark, yet somehow light-hearted, Stewart’s directorial debut is a running start for him if he wishes to continue with directing. Though the editing needs to be less obvious and the writing a bit cleaner (the ending wrapped up a bit too neat and tidy for its own good), Stewart already expresses his own style in directing with his well-timed humor and interesting themes. “Rosewater” is not Stewart’s discouraging failure in addressing serious issues with pure slapstick and satirical monologues. It’s Stewart’s honest attempt that leaves the audience wondering, “I wonder how he’ll approach his next film.” The audience may not be enthusiastic, but we’re still interested.

Rating: 3.5 stars