It’s rare to see percussion at the forefront of American music. Because of this, many American radio listeners are not knowledgeable of the dynamic, vibrant possibilities that exist within percussive music. Interestingly, there are some countries, like India, that often place percussion as the focal point of a performance. The tabla drum, which consists of two drums played by each hand, is one of the most popular instruments in Indian music and is often played as the centerpiece of a performance. It is considered the most versatile percussive instrument in India because of its ability to suit multiple musical styles.

On Feb. 5, 2016, UCR was fortunate enough to have Abhiman Kaushal, one of the most prominent figures within the tabla world, to perform six compositions at the University Theatre. Kaushal is the director of North Indian classical music at UCR and has accompanied most of the leading musicians in North Indian music.

Following a brief introduction by UCR Professor and Department Chair of Musicology Walter Clark, five men ambled onto the stage with their palms pressed together to express appreciation to the crowd. Their eyes remained fixed on their instruments, rather than the crowd, in a modest gesture, as though to indicate that their goal was to provide a meaningful, transcendental experience through music.

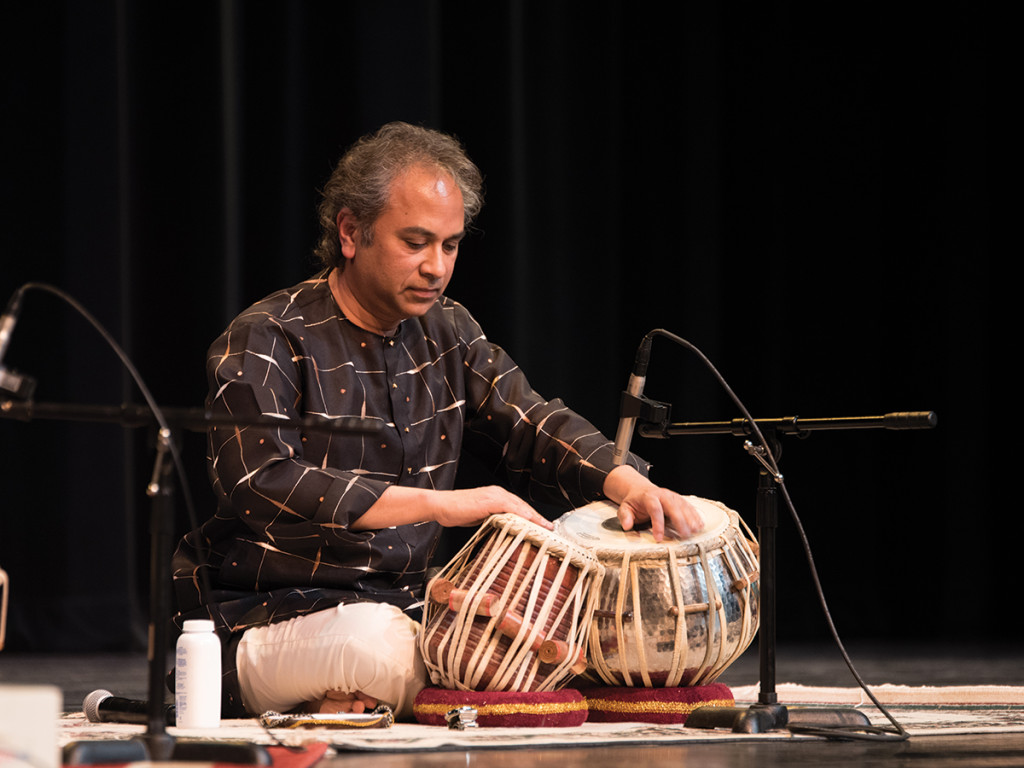

The instruments included a swarmandal (a harp-like instrument), three tabla drums and a sitar. The tabla drums rested on plump-looking pillows that were various shades of red and brown, and the men were calmly seated, cross-legged, on red blankets, with the exception of the man at the center of the group, Kaushal, whose blanket was ivory white.

Following a pre-performance ritual consisting of tuning the drums with a small hammer, Kaushal introduced the crowd to his assisting musicians. On the tabla drums were Miles Shrewsbery and Kaushal’s good friend Revi, playing the sitar was Nasir Syed and providing the swarmandal as well as vocals was Vignesh Manohar.

Kaushal then introduced the audience to the tabla instrument itself.

“The tabla is the most common accompanying instrument in North Indian music. It has its own language, its own repertoire,” he explained.

Within this unique “language” were six style compositions that he would play for us. “Compositions” refer to ordered sets of “mantras,” or uttered words that are believed to have spiritual power. The first composition they would play was named “peshkar,” a basic tabla composition.

The performance began with the swarmandal and the mantras of the vocalist. The melody he sang repeated every 15 seconds, but this re-occurring pattern wasn’t tiresome like the repetitious choruses of mainstream music. This repetition enhanced the performance by establishing a constant for the vivid improvisation of the tabla drums. After about 10 minutes, the sitar joined in with an accompanying melody.

Finally, after about another 10 minutes, Abhiman gently patted his drums and began with the peshkar beat. While he patted the bayan with the flat of his left thumb resting on the surface, his right hand beat the dayan in an intricate pattern that almost resembled typing on a keyboard. Each drummer played one at a time, then would switch off to another drummer in a variable pattern. What was interesting about the composition of the instruments was that the vocals and strings provided the backing instrumentals to the percussion, which is the reverse composition of American mainstream music.

Following each composition, the crowd would offer an enthusiastic round of applause as well as expressions of awe and amazement. The five musicians didn’t let the applause distract them, and instead, resumed by smiling at one another and clapping their hands to support the beat of whoever was playing. It was all a matter of communication in which the pedestal was passed from one drum to another.

With each progression of style, the tempo grew faster, and the drumming patterns became more complex. When the group reached the sixth and final composition, all three of the drummers played simultaneously at an unexpectedly rapid pace. It sounded like there was thunder in the room, but everything emanated from six small drums, and there was not one gap of a second that was not filled with booming euphoria.

With a sudden, theatrical ending, all three of the drummers lifted their hands suddenly and stopped, and the percussive thunder was replaced by the beating hands of the audience. The crowd provided a hearty standing ovation, and Abhiman and the four assisting musicians humbly placed their palms together. There were no concluding statements, but there was no need for words to seal the memorable performance. The performance proved that words are not necessary in creating a sensational, spiritual experience that can otherwise be communicated through rhythm and melody.