The average temperature at UC Santa Barbara in the month of April is exactly 69 degrees Fahrenheit — not too hot, and not too cold, but just right. The mild temperature matches the school’s placid demeanor, whose students party late at night but also relax to the lapping of the waves and enjoy the quiet calmness of coastal California. Amid the tranquility, however, a debate is heating up over the limits of free speech — and UC Santa Barbara’s campus policies that unfairly restrict it.

The spark that lit the powder keg occurred on March 3. A group of pro-life protesters from Survivors of the Abortion Holocaust came to advocate their perspective, showing photographs of lifeless fetuses and passing out pamphlets to passerby in a so-called “free-speech zone” on campus. Debates about abortion almost always fire people up, and one such person was UC Santa Barbara associate professor of feminist studies Mireille Miller-Young, who saw the display as she was passing by. Arguing that students were finding the images “disturbing” and that she was “triggered” by the display because she herself was pregnant, tensions flared as Miller-Young demanded the protesters take their signs down. The protesters countered that they had a right to free speech and refused.

What followed was a frenzy of action, with Miller-Young allegedly seizing one of the protesters’ signs, fleeing and entering into a small scuffle with the protesters attempting to recover the purloined sign. The entire chase is on video, and to make a long story short, Miller-Young escaped her pursuers, a 16-year-old protester was injured, the sign was destroyed and the incident was reported to the UC Santa Barbara Police Department.

However, the issue has done anything but flame out. Miller-Young has been charged with three misdemeanors, including battery, vandalism and robbery, but last Friday pled not guilty. The Daily Nexus, UC Santa Barbara’s campus newspaper, has published letters to the editor asserting that the protesters were out of line by using over-the-top rhetoric and disturbing imagery. Meanwhile, the pro-life group has started a petition to fire Miller-Young, while some UC Santa Barbara students have counter-petitioned, urging the UCSB administration to stand in support of the professor.

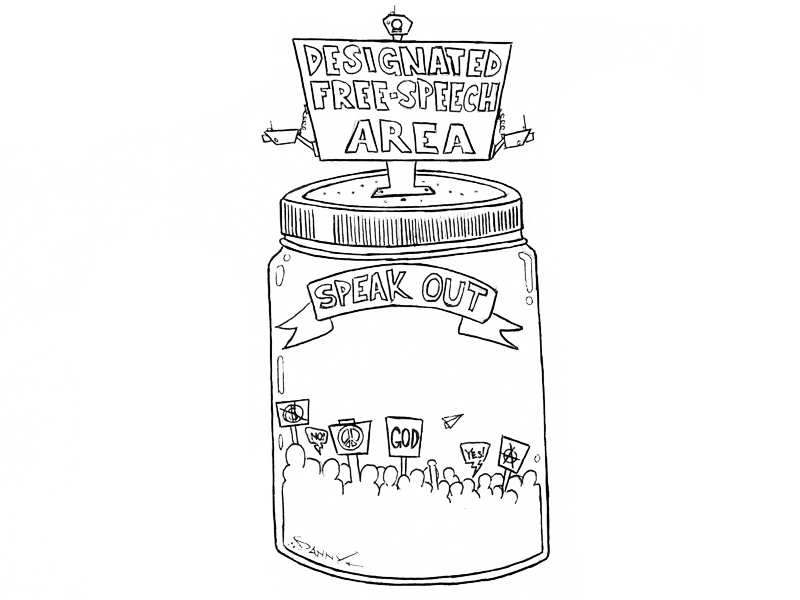

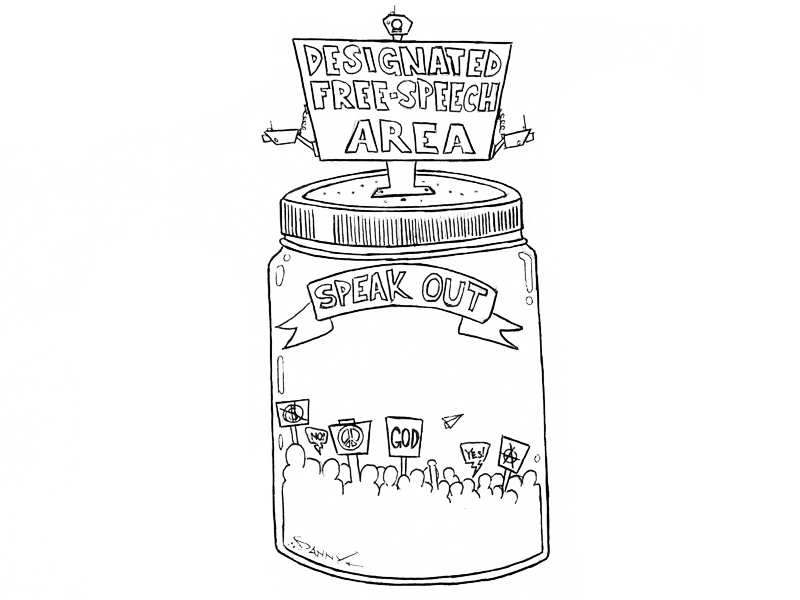

Yet, wherever you stand on the issue of abortion, a more troubling aspect of this case has been lost in the shuffle; namely, how problematic the idea of a “free speech zone” is in the first place. Although court rulings have found that universities may place time, manner and place restrictions on campus gatherings, limiting students and other members of the community to a designated area to express their speech seems antithetical to having the right to speak your mind without fear of repercussions. Regulating where free speech can be expressed is one worrisome step away from regulating when it can be expressed, a dangerous infringement of liberty.

The website for the UCSB police department notes that, according to campus policy, “specific areas are designated for public meetings” and are reserved on a “first come, first served basis.” This rule effectively means that protesters must plan their protest far in advance — which is no doubt in place for numerous beneficial reasons, such as keeping protesters safe and protecting students’ privacy. However, it also has the side effect of rendering spontaneous expressions of outrage or excitement against the rules, even if those are legitimate responses to an emotional event.

Limiting people to certain areas to protest cuts against the very idea of universities, institutions that were founded to promote the free exchange of ideas and broaden horizons. Only if conversations about all topics are able to be held without fear will universities truly be able to accomplish their mission to educate and prepare students for the world. By blocking free speech and limiting it to “free speech zones” UCSB is preventing students from adequately engaging in the very discussions a university is supposed to promote.

This is even more troublesome because as a public university, the UC is open to the public to use. There is no identification system at the front gates that permits only university staff, faculty and students to enter. It is a public space for the public to use, evident enough when UCR hosts symposiums or community service events that the Inland Empire community eagerly attends. The public invests in the UC system by providing taxes, students, participation and funding. As such, the public has the right to benefit from the services the university provides — shouldn’t we also have the right to speak freely at a university owned in common by the people?

There are, of course, limits to free speech. Speech that endangers the safety of others is not permitted in a public space — shouting “Fire!” in a crowded theatre, for instance. Likewise, the UC Santa Barbara police state that under time, place and manner restrictions, “Regard for others’ privacy shall be observed, and reasonable precautions shall be taken against practices that would make persons on campus involuntary audiences.” These are reasonable restrictions that prevent undue harm from coming to passerby and protesters themselves, who may be voicing unpopular opinions.

But UC Santa Barbara can do away with the antiquated idea that protesters must be boxed in to a specific location to be able to protest. Allowing free speech on campus everywhere would create a less stifling atmosphere, but could still maintain students’ privacy and enable the broad exchange of ideas that universities are known for. UCR has a much more lenient, common-sense approach that permits people to exercise their first amendment rights on “campus grounds generally.” There are exceptions, as there are for any policy. But this is far less restrictive than having the cage of a “free speech zone” imposed on the campus from above.

In the wake of the Miller-Young incident, UC Santa Barbara’s Vice Chancellor of Student Affairs, Michael Young, sent out a campus-wide email espousing the virtues of free speech. “Freedom and rights are not situational,” Young writes. “We either have free speech or we do not.” Young should follow his own advice and advocate for UC Santa Barbara students to receive the freedom of speech they deserve — the ability to speak their minds anywhere on campus, without being hemmed in by the boundaries of a “free speech zone.”