This article contains spoilers for George A. Romero’s “Night of the Living Dead,” “Dawn of the Dead,” “Day of the Dead” and parts of “Martin.”

Ghouls, monsters, walkers, runners, flesh eaters, walking dead, living dead. There’s more ways to refer to zombies than there are shades of gray, due in no small part to the overwhelming ubiquity of these creatures in pop culture. But there was only one George A. Romero — the man who really brought forth the zombie as we know it into popular culture — and his passing on July 16 hit hard for those who remember the impact he had on pop culture. It’s easy to write off Romero as the man who spawned a horde of brainless gore fests in the guise of feature-length films, but to do so would ignore the brilliance in his original trilogy’s social commentary and the man’s wonderful charm.

Before Romero gained notoriety for being the immoral director of the now-classic progenitor of the zombie film, “Night of the Living Dead,” he was a director of commercials and short films, forming his first production company, The Latent Image, in the early ‘60’s. One of the commercials created under Latent Image, a spoof of the 1966 film “Fantastic Voyage,” necessitated his crew to upgrade their equipment and purchase 35mm film cameras, which then gave way to the notion that they could produce their own feature-length films. Two years and one abandoned “Virgin Spring”-esque screenplay later, Romero and company embarked on creating their very own film.

“Night” epitomized DIY filmmaking before DIY filmmaking was a thing. Aside from Duane Jones as the pragmatic male lead, Ben, just about every other cast member of the film was new to acting. Makeup effects were shoddy — but charming in their improvisational blemishes — fire safety was near nonexistent and the crew didn’t all exactly know what to do. It was uncommon for any crew member to serve just one role in the film as many, including producers and screenwriters, also took on acting roles as the film’s horde of zombies.

Romero didn’t invent zombies per se; “zombies,” a term deriving from Haitian folklore, referred to reanimated corpses brought back to life through necromancy, serving as a thrall to whoever used magic to revive it (think “White Zombie,” “Serpent and the Rainbow”). What he did do, however, was create a monster that abided by certain rules, relatively loose rules that we see in contemporary zombie media like “The Walking Dead” — slow movement, some distant memory of their former life and an insatiable appetite for human flesh. The ghosts in “Carnival of Souls,” a favorite of Romero’s, provided a reference point for how these undead would act. Over time, these rules have changed and been liberally recontextualized to fit a more scientific approach (“The Last of Us,” “Resident Evil”), aiming to suit an audience of gore fiends and adrenaline junkies (Zack Snyder’s’ “Dawn of the Dead” remake, “28 Days Later”) or to serve some laughs (“Shaun of the Dead,” “Zombieland”). There’s no exhaustive criterion to distinguish how a zombie differs from any other flesh eating stiff, but a zombie is now as recognizable as a werewolf or mummy.

Zombie fatigue has been sweeping media industries for years now, and while the popularity of “The Walking Dead” may prove contrary, it’s not uncommon for a new zombie-based IP to be met with lukewarm reception. But in 1968, “Night” was fresh, it was terrifying, it was graphic and it was (unlike many if not most zombie media today) smart. Within the film’s unflinching depiction of matricide was a vision of utter bleakness reflective of the period’s tempestuous public consciousness. Racial injustices at home fought hand-in-hand with an unfavorable war in the eastern nation of Vietnam to divide the United States into isolated ideological camps full of rage and unrest, developing an “us” vs “them” mentality among many.

Speaking to the film’s subtext, Romero, in an interview for the 2012 documentary “Birth of the Living Dead,” stated, “We were aware of the time and the anger of the 60’s … We thought we had changed the world or were part of some sort of reform then all of a sudden it wasn’t any better, wasn’t any different.” Hence the phenomena of a world doomed to be brutally consumed by shadows of its former self. It’s no surprise then that the end of “Night” parallels the ugliness of its time when Ben gets shot square in the head by a group of armed men aiming to liberate survivors. The casting of Jones as Ben was by sheer virtue of talent, though one can imagine how the impact of a black man getting mistakenly murdered (by a group of men easily mistakable for a lynch mob) would be dampened had Ben been played by a white actor.

God changed the rules. That’s the only explanation that I need. No more room in hell… It’s some sort of permanent condition, unless we redeem ourselves.

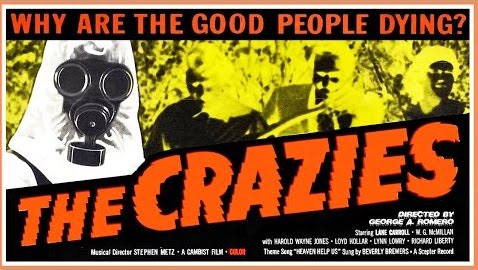

Following his directorial debut, Romero would go on to direct four more films before revisiting the living dead series with “Dawn of the Dead” in 1978; two of the four — “The Crazies” and “Martin” — further demonstrated how adept Romero could mesh horror with desolate social commentary.

While 1973’s “The Crazies” bore more than a few similarities to “Night” in its examination of a town overrun with a virus that causes victims to turn murderously mad, the chief goal of this film was not to terrify the audience with a shocking display of violence evoking the failures of society. Instead, “The Crazies” took aim at the role of an increasingly militarized United States: The virus, dubiously named Trixie, is the result of a chemical weapon leaking into a town’s water supply, forcing the Army to set up a quarantine zone which pits the armed townsfolk of the rural Pennsylvania town against the hazmat-suit wearing Army soldiers. Of course, it wouldn’t be a Romero film without a depressing ending, best represented by the end credits song by Beverly Bremers, “Heaven Help Us.”

Romero’s favorite of his films, “Martin,” is one of the great Romero horror flicks to put the apocalypse on hold and plant both feet in the real world. Sort of. It’s about 20-something year old Martin (Romero regular John Amplas) who moves to Pittsburgh to live with his cousin Tateh Cuda, an old school Catholic who firmly believes Martin is a vampire. The premise reeks of 70’s cheese, but it’s the most grounded of Romero’s efforts to cynically address the failures of man. Is he really a vampire? It’s not certain. Though Martin, who may or not be mentally ill, has been told his whole life of the curse of “the evil ones” that’s plagued him and his family, Romero boldly presents evidence toward the contrary. “There’s no magic in the world,” Martin tells his cousin when presented with a cross and cloves of garlic. But be it a result of dark magic or merely a self-fulfilling prophecy, Martin’s murderous habits add some complexity to the film, without taking away from the empathy the audience has for the character.

With aide from Italian giallo filmmaker Dario Argento, Romero was able to finance “Dawn of the Dead,” a full ten years after the release of “Night.” Like the film that preceded it, “Dawn” is a zombie horror film that puts its characters in a bubble meant to represent a larger part of western society. In “Night,” the prevailing issue was racism and Vietnam. In “Dawn,” the shopping mall setting is a stage from which Romero can frame a mirror to and critique the consumerism afflicting the masses. The satire works without ever needing it to be embedded into the plot, working organically and relaying itself to the audience without the need to pander. When a character asks, “why do they come here?” another asserts, “some kind of instinct. Memory, what they used to do. This was an important place in their lives.”

One of the many great aspects of Romero’s first three zombie films was the progression in storytelling each sequel represented. Though “Night” is a beloved classic, the ideas in “Dawn” and their execution make it a stronger film in every single regard. The main cast of characters are given more personality and depth which predicates their outcomes. Roger (Scott Reiniger) is a SWAT deserter whose arrogance and thrill of the kill results in his demise when he finally gets bitten; as Flyboy (David Emge) slowly grows attached to the mall and attached to the illusion of wealth, he risks his life trying to defend from the group of raiders invading the mall and finds himself surrounded by a crowd of ghouls; both Peter (Ken Foree) and Flyboy’s pregnant girlfriend Fran (Gaylen Ross) narrowly survive only out of their own commitment to survival and lack of attachment to the mall.

“Day of the Dead” is arguably less so so Romero’s masterpiece and more so Tom Savini’s. Savini’s singular makeup effects are more foul and convincing than nearly everything in today’s contemporary landscape of horror films, from the scabbed decomposing flesh of the dead to the crimson innards that spill abundantly throughout the film. But what’s striking about “Day,” barring the mature language and visceral gore is, despite its bleakness, it ends on a similar note to “Dawn” with its protagonists escaping on a helicopter — this time, however, without the ambiguity of their destination. The surviving trio of “Day” finds their own dream island before the credits roll, but it’s only a matter of time before their inevitable deaths.

In Romero’s final film in the series before revisiting it 20 years later with 2005’s “Land of the Dead,” the night has turns to day but the horrors have only grown. This time around, he’s tackling a lack of communication as causing the death of civilization as we know it. “Day” is peak “the world is doomed and it’s our fault” Romero, illustrating this best with the notion that zombies are now easier to empathize with than most of the human cast. Intentional or otherwise, the trilogy was on course for this — as “Dawn’s” tagline states, “when there’s no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth.” Then what does that make the earth?

Since “Day,” Romero went on to direct seven more films before his passing in July. For a filmmaking icon most known for pessimistic horror films, he was rarely ever seen not smiling and attributing his renown to those that helped him along the way. Never keen on the violence he presented in his films, he favored using the horror elements as allegories for important criticism. Surely his films were dour, but there was always some degree of hope in the good guys, the survivors who fought for the endurance of their neighbors; in the end, though, maybe that bit of good wasn’t enough to save the day. The Bronx-born Pittsburgh native’s legacy goes beyond expanding the horror genre lexicon and adding a new baddie for pop culture to implement and spoof ad nauseum, leaving behind a tactile imprint on the landscape of filmmaking both big studio and independent.