Well, it was great while it lasted.

This is the final edition of the Highlander. As the University of California, Riverside marches ever onward to secure its place in history as the premier university of the nation, it has become clear that the Highlander is no longer needed by the community we serve. The purpose of the Highlander has been to inform the campus by serving as an outlet for true stories to be told, but all stories have a beginning and an end—and the story of the Highlander has reached its close.

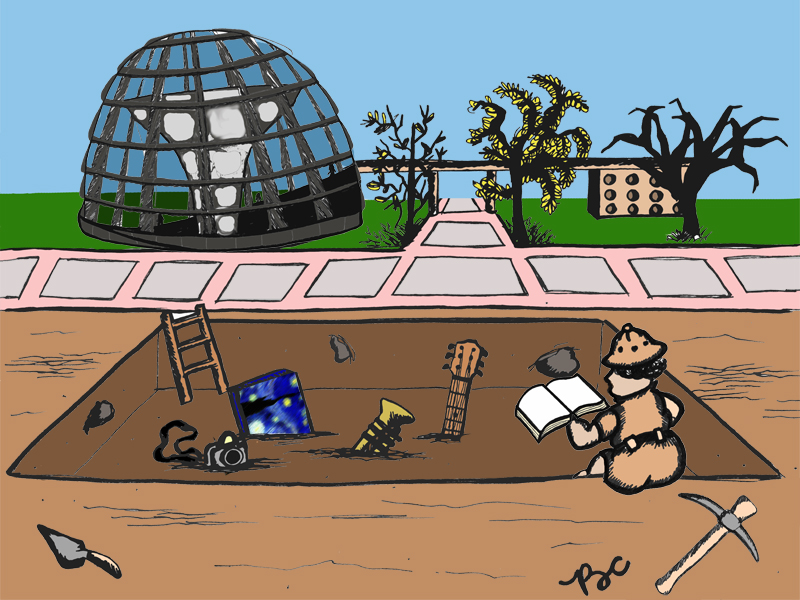

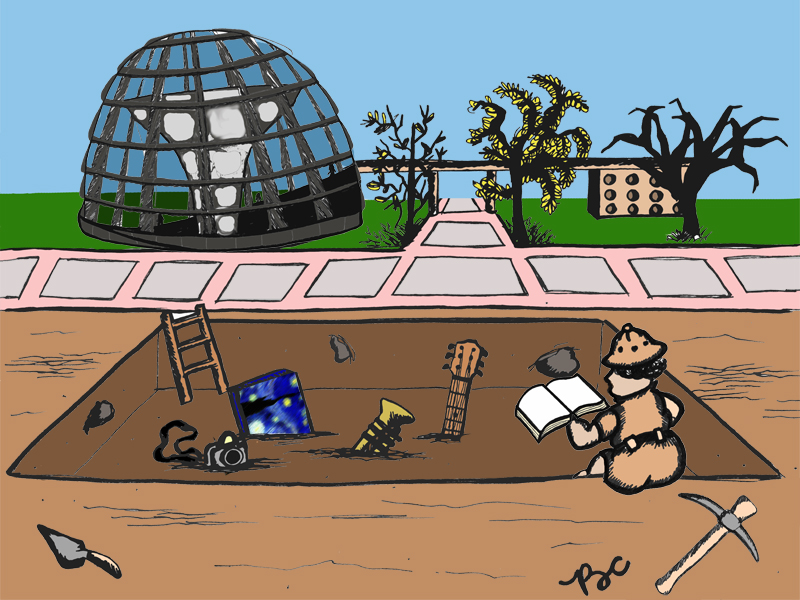

In a physical sense, the story of UCR will continue, even without the Highlander. But it is fair to say that the UCR that once was no longer exists. When Chancellor Xavier Genesis gives his speech next week to commemorate the bulldozing of HASSLE’s final stronghold, Watkins Hall, to make way for the new CNAS Dome, it will mark the final passing of one of UCR’s greatest traditions—its endeavor to achieve excellence in the arts and humanities.

Yes, it may be hard to believe, but UCR has had a storied legacy of achievements in the arts. In 1974, UCR’s arts and humanities programs were ranked fourth in research achievement out of all the universities in the nation. UCR was even known as the Swarthmore of the West. UCR was, for much of the history of the UC, the only college to offer creative writing as a major, and was the first university in the nation to offer a Ph.D program in dance history. UCR counts Pulitzer Prize winners, the Poet Laureate of the United States, the first Latina governor of California and artists whose works hang in the Louvre among its alumni.

This pursuit of knowledge of the humanities and the arts and the social sciences was for good reason. Even if they may not be considered the most profitable or practical majors, they are vital to informing our view of the world we live in. Each is more than just an interesting hobby—they help better society in a great number of ways.

Just as an entomologist can help develop a more effective pesticide, a psychologist can help determine the best way to treat a schizophrenic patient. A political scientist can help groups plan the most effective course of action to allocate funds for a philanthropic cause just as well as an engineer can use those funds to construct the sturdiest building.

Yet the purpose of the humanities and the arts extends beyond mere utility. And our society, in the blind pursuit of profit and practicality, seems to have forgotten that life is more than a series of interlocking cogs and gears. It is far too complex to be distilled into a blueprint and measured with exact specifications. Humans are too unique and too individual to be reduced to data points on a graph or equations in a math problem.

But that’s okay.

It is these complexities, these intricacies, these differences that the humanities and arts alone can raise. What does it mean to be human? How do we treat others in society? How do we decide who we want to be and what we want to do? Scientific study alone is insufficient to answer these questions.

Novels, biographies, paintings and sculptures—each allows us to detach ourselves from our small plane of existence and experience the lives of people very different from ourselves. We see the world through the eyes of a single working mother struggling to feed her children as a city decays around her, and empathize with her plight. We hear the cheering adulation of joyous crowds celebrating the emancipation of a city under siege by crime and share the triumph of our human compatriots.

Each of these conveys something universal about the human experience that data aligned on a graph cannot. Through these multifarious experiences, we learn more about ourselves and the way we see the world and interact with others in it. There is a reason stories have been passed down from generation to generation and artworks have been crafted for so long in human history. They have an inexpressible power that speaks to experiences uniquely our own.

But more importantly, they allow us to peek into the world of others’ experiences and understand a different world than the one we normally inhabit every day. And through that, we gain a deep understanding of what others’ lives are like, one that we could not have gained by remaining in our own body and experiencing the world through only our eyes. We as humans do not exist independently of one another. We interact with others every day. And we interact better when we are able to empathize with our kin. The humanities alone allow us to do this.

With these insights into other peoples’ lives, we become more aware of our actions and can evaluate their impacts on the greater society. Only when we engage in this type of evaluation are we able to achieve a state of thinking that allows us to decide what actions are morally just and which are unjust, something Science alone cannot do. Science does not provide us with the answers to moral questions—the humanities can.

In the midst of first constructing the atomic bomb his theory of relativity helped create, Albert Einstein remarked, “Perfection of means and confusion of goals seem—in my opinion—to characterize our age.”

That could just as easily be said about us in the year 2113. We have devoted our resources to figuring out the most efficient way to generate electricity and how to engineer safe, high-speed transportation systems. But Science doesn’t tell us what to do with the things it has helped us create. And for all the inventions, creations and constructions society has generated, only the humanities can tell us what goals we as a society should strive for.

The last bastion of art and society, HASSLE, will soon be removed from UCR, and it is discouraging to imagine a UCR that does not teach the liberal arts. As society marches onward, and the humanities are swept below the surface of the earth to be discovered by aspiring archaeologists centuries into the future, we must always remember that the arts and humanities have nurtured our society to maturity. Our world is incomplete without it.